The Monroe Doctrine

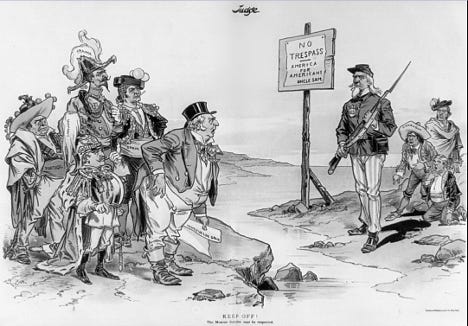

For almost 200 years, the United States has integrated the Monroe Doctrine into its foreign policy and the American psyche. It lays out the basis for our involvement in our Latin American neighbors' domestic and foreign affairs.

I will quote the actual document below. The main thrust is that the American continent should be free from European interference, and the United States will enforce this politically and militarily. The document defining this is long and complex, but the introductory statement lays out the thrust of the Doctrine. This became American policy in 1823.

The occasion has been judged proper for asserting, as a principle in which the rights and interests of the United States are involved, that the American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers.

We owe it, therefore, to candor and to the amicable relations existing between the United States and those powers to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety. With the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power, we have not interfered and shall not interfere. But with the Governments who have declared their independence and maintained it, and whose independence we have, on great consideration and on just principles, acknowledged, we could not view any interposition for the purpose of oppressing them, or controlling in any other manner their destiny, by any European power in any other light than as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States.

In modern terms, the doctrine was America’s statement that Europe should stay in its lane.

History of the Monroe Doctrine

President James Monroe laid out the Monroe Doctrine on December 2, 1823, during an address to Congress. It was a defining moment in the United States foreign policy, establishing the Western Hemisphere as a sphere of influence free from European colonization and intervention.

The doctrine was born out of a desire to protect the newly independent Latin American nations, which had recently gained independence from Spain and Portugal, from the threat of European re-colonization. The Napoleonic Wars had ended, and the Congress of Vienna laid out the new world order as European powers defined it. Three major powers on the continent were Prussia, Austria, and Russia, all of whom wanted to save Monarchies from the march towards independence, particularly the new nations that were part of the Spanish possessions.

Monroe saw the strategic advantage of establishing the U.S. as the dominant power in the Americas. The doctrine had two main principles: non-colonization and non-intervention. It declared that any European attempt to colonize or interfere in the affairs of nations in the Americas would be considered an act of aggression requiring U.S. intervention.

At the time it was established, the American forces could not enforce it with the military they had. Paradoxically, the Monroe Doctrine was enforced by the British Navy. The British had very few colonies in the Americas and were most interested in trade. Keeping the continental European powers from expanding their empires or reconquering newly independent countries benefited British goals of increased freedom to trade with the Americas.

Although the Monroe Doctrine is often derided today, it ultimately did help most Latin American countries with their fights for independence. It also enabled the United States to dominate the continents for 150 years, long after the countries could define their own paths.

Past Uses of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was used throughout the 19th and 20th centuries to justify U.S. actions in the Western Hemisphere. In the late 19th century, it was cited to support U.S. intervention in Latin American affairs, including the Spanish-American War in 1898, during which the U.S. emerged as a colonial power.

The biggest challenge to the Monroe Doctrine in the 1860s was the French invasion and subsequent rule of Mexico. This occurred in 1862 when the Civil War occupied the United States. The United States could not respond when this occurred, but it was a priority after the war ended. After the American Civil War, the United States stationed military along the US-Mexican border and demanded the French withdraw. The French ultimately did pull out of Mexico, abandoning the French Dictator Maximilian – after which he was overthrown.1

In the 20th century, President Theodore Roosevelt used the Monroe Doctrine to define the right of the U.S. to intervene in Latin American countries to stabilize their economies and political systems. This led to numerous interventions in countries like Cuba, Panama, Nicaragua, and Haiti. The doctrine was also referenced during the Cold War, particularly during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, as a justification for opposing Soviet influence in the Western Hemisphere.

In 1983, it was part of the justification for the US invasion of Grenada. While the doctrine is no longer acknowledged, it is still a guiding principle for US foreign policy and US public support.

Going Forward – Is it still relevant?

While the Monroe Doctrine has historically affirmed U.S. dominance in the Western Hemisphere, it is obsolete in the current political climate. One major issue is the view of American imperialism. Many Latin American countries see the U.S. as the perpetrator of interventionism and control, not as their savior.

The idea of a “Monroe Doctrine” or contemporary version is ludicrous today. Latin America works with foreign powers through economic investments and partnerships. China, in particular, has made significant economic and political inroads in Latin America.

The U.S. is trying to navigate this shift in global power dynamics while maintaining its regional strategic interests. However, American political and military responses often rely on the ideology of the Monroe Doctrine, even if it is not explicitly mentioned. The currents recent threats’ recent threats to Colombia by the current administration have reinforced this opinion. The threat of taking the Panama Canal by force also belies the U.S. as a protector.

The Monroe Doctrine is no longer the U.S. position concerning the Americas. However, the idea that America can control the destiny of Latin America remains lodged in our collective memory. The doctrine’s legacy continues to shape U.S. interactions in the Western Hemisphere. The U.S. must evolve to address modern geopolitical realities and foster more collaborative and respectful international relationships. But a profoundly ingrained ideal is tough to repudiate.

Interestingly, the first successful attack of the Mexican forces against the French was on May 5th - which is Cinco De Mayo.