(Note: I have not posted in a while due to two factors. 1: The idea that AI can do a better job than I can has deflated my sense of pride in this. 2: The US election depressed me. A depressed Scooter is not a motivated Scooter.)

Dams

Dams are an ancient technology and often wonderful things. They bring multiple benefits: prevent flooding, provide steady irrigation water, drive power (first waterwheels, later hydropower and electricity), open waterways to commerce, and more.

There are also downsides, such as destroying habitats, ruining fisheries, and displacing some residents. A new cost/benefit analysis favors extremely large hydroelectric projects.

The most contentious issue is the damming of a river critical to downstream countries. This is a beggar-thy-neighbor form of growth, where the local population benefits while downstream nations bear the drawbacks. It causes geopolitical problems that threaten to escalate into physical conflicts.

The newly approved MeDog Dam in China above India is the latest dam to cause international tensions.

This post will describe three scenarios as a case study of the problems. It will also look at some planned installations that are still in flux and might cause extensive problems in downstream nations in the future.

Case Studies on Current Dams

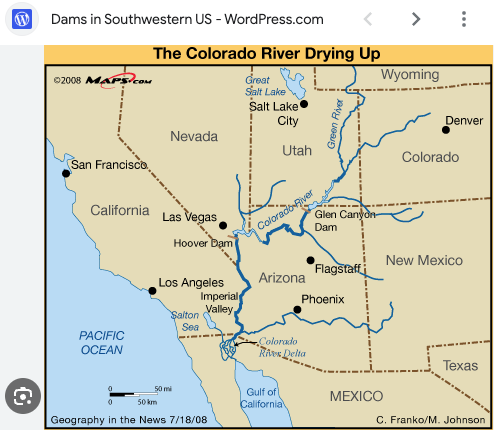

Case Study 1: Hoover Dam on the Colorado River in the US

The Hoover Dam was designed to provide a consistent water flow to southwestern US residents. The interesting thing about the Colorado River is that the dam affects the nations of Mexico and the United States. The politics of distributing that water also affects various states that traditionally use it. In this case, water distribution is both an international and intranational issue.

In the 1800s, the river flow in Mexico was over 1,200 cubic meters per second. Then, the US began controlling the Colorado River and turning a desert into an agricultural heartland. In 1901, the US built the Alamo Canal through Mexico, diverting river water to farmland in California's Imperial Valley. Mexico's use of Colorado River water grew over time in the same way water use in the southwestern US grew. For example in 1922 Mexico used about 500,000 acre-feet a year. This grew to 750,000 per year when the Hoover Dam was finished in 1935 and 1.5 Maf (Million-acre feet) by 1944.

The growth of water usage on both sides of the border increased tensions between the two countries. In 1922, the first compact for water rights assumed that 2 Maf1 of water would be available for Mexico to use. In 1930, a deal failed between the countries when Mexico claimed 4 Maf and the US offered 750,000 acre-feet.

In 1944, an agreement was reached that Mexico would receive a minimum of 1.5 Maf. However, there are ongoing complications between the US and Mexico regarding water quality. For example, if a field is irrigated in Arizona, does the runoff, now contaminated with fertilizer and runoff chemicals, count as “river water?” Colorado River management still flares up when droughts occur.

Case Study 2: The Ethiopian Grand Dam

Since its construction in 2011, the Ethiopian Grand Renaissance Dam on the Blue Nile has been a source of regional conflict. In Sudan, the Blue and White Nile combine to form the Nile. Ethiopia completed the long-discussed dam on the Blue Nile in 2023 and finished filling it with water in 2024. The dam has long been a bête noire of Egypt and Sudan. Both downstream countries use the Nile as their primary source of water.

The Ethiopian argument for the dam is that it will provide electricity and a steady water source. The Blue Nile's flow can vary greatly; in some years, it even dries up for a short time. The dam ensures there will be water for Ethiopian interests. It currently produces 1550 MW (megawatts of energy), equal to about 911 million barrels of oil, higher than the yearly oil output of Venezuela or Great Britain. The number will rise over time as new generators are brought online.

The two downstream nations, Sudan and Egypt, have claimed that this dam will be adverse to their people and water needs. Sudan has alternately opposed and supported the project. The civil wars in Sudan have produced changes in governments with varying support and interest in the project.

Egypt has consistently opposed the project. Egypt receives 85% of its water from the Nile, and allowing another country to control this is unacceptable to the Egyptians. Unacceptable, but now irrelevant, as the dam is completed.

Threats and counter-threats between the two nations did not dissolve into open conflict due to the mediation efforts by outside parties, particularly the US.

Interestingly, Egypt built the Aswan High Dam, which relocated over 100,000 people upstream in Sudan. Although the dam was controversial in Sudan, Egypt ignored the objections.

Case Study 3: The Dams Along the Mekong River

The damming of the Mekong River In Southeast Asia has caused international conflicts in the nations downstream from China. China has built 56 major dams in Chinese upstream waters of the Mekong.

The Mekong is the primary river artery in Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam, serving 65 million people. Despite China's assurances, the Mekong and countries along the river have suffered adverse effects downstream of the Chinese dams.

The dams have reduced fish populations in the downstream Mekong river nations. The fisheries supply need protein for the local populations.

Damming has reduced downstream seasonal flooding, which is an unexpected issue. Because the Mekong is a seasonal river, annual flooding brought new sediment and silt downstream to replenish farmlands. The dams reduce or stop this soil recharge.

These dams have also relocated between 100,000 and 280,00 people, and hundreds of villages. These problems will be even worse with the new Medong Dam project in China, which is currently under construction.

The Mekong River still has numerous dams planned in both China and downstream nations.

The Planned Medog Dam

The newly approved Medog Dam in China is already causing international tensions.

The massive Medog dam in China is planned at the Great Band on the Brahmaputra River - called Yarlung Tsangpo in China. The construction is controversial in India, Bangladesh, and Bhutan. China has approved this mega dam above India to generate hydropower.

The dam will affect the downstream nations that rely on the river. It will reduce the flow as it is filled, and China might keep any water from entering the lower Brahmaputra basin during a drought. It will also delay India’s planned dam lower on the river. With a reduced flow during droughts, the dam would reduce irrigation in India, lowering agricultural output in nations already facing problems of rising populations.

India and China are two great powers that have clashed over the border since the independence of India and Chinese control over Tibet. India sees a threat from the river in geopolitical politics. If the Medog dam is built, China could reduce or stop water flow out of China and into India. For two adversaries, this is unacceptable to India despite India having no leverage to stop construction.

Another potential issue unique to the Medog is that the Tibetan plain is subject to large earthquakes. A break in the planned Medog dam will overwhelm the lower reaches with flooding.

How to Address Issues with Multinational Dam Building

The UN treaty, the Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, defines how to manage the impact of new dams on all affected countries. It is a good start, but China, India, Egypt, Ethiopia, and the United States are among the countries that have not signed the agreement.

The convention was also created before the effects of climate change were apparent. Instability caused by climate change will only make dams more important as weather patterns are disrupted. To understand the future of this agreement, look to the United States. Some of our rivers cross into Mexico or Canada. The United States refuses to change water projects due to the possible objections of these international neighbors. However, Western states look at the possible importation of fresh water, which Canada controls. This might change the US outlook on international norms.

In short, nations upstream will not abdicate their ability to control water access despite the effect on downstream nations.

Mfa - Million-acre feet of water