For decades now Americans have not had to “deal” with the economic issues of inflation, stagflation, or deflation. The United States and most major developed countries attempt to manage inflation and keep it at 2%. They have been so successful, until Covid, that many of us have ignored that part of the economic equation. For many of us, the ties between interest rates, inflation and prices in general are opaque because we have not had to deal with these.

In this piece I try to describe these terms for simply laymen – like myself. Not for some esoteric love of knowledge, but because they have impacts on our lives, now that the time of easy management has come to an end.

We understand that inflation as we know it is a relatively new phenomenon. Before the easy movement of money and goods between nations, inflation was not an indicator we could affect.

A quick and simple definition of terms

Inflation – Inflation is the measurement of the year-over-year increase in prices for goods, services, and employees. So let’s look at how the inflation rate works, starting with $100 dollars:

Year Cost of Goods inflation rate Increase this year Next year Cost

2000 $100.00 2% $100.00 x .02 = $2.00 $100.00 + $2.00 = $102.00

2001 $102.00 2% $102.00 x .02 = $2.04 $102.00 + $2.04 = $104.04

2002 $104.04 2% $100.04 x .02 = $2.08 $104.04 + $2.08 = $1.06.12

Manufacturers and Services companies like a steady inflation rate because then they can easily estimate costs going forward.

Stagflation - Stagflation occurs when the economy is growing slowly, the inflation rate is high AND unemployment is high. Higher rates of inflation normally put more money in the economy and the economy drives more jobs. Stagflation means that despite higher prices – and subsequent larger economic drivers – unemployment stays stubbornly high. This is a rare condition and was thought to be impossible until the oil shock of the 1970s brought stagflation to the United States.

Deflation – Deflation is the opposite of Inflation. Every year the price of goods falls. This sounds like it might be a great thing for consumers, but it stifles the economy. If a consumer sees something for sale for $100, but they KNOW it is going to fall in price – they will wait to buy it. That works great for things like TVs or Computers or Houses (for a while), we have all waited for a fall in price. But when everything falls in price, consumers stop spending expecting prices to fall more. If everyone in a country stops spending, then goods will stop sellers and producers stop producing and the economy will slow down to a crawl.

Central Bank – A Central Bank is the bank that is in charge of regulating and releasing new money. It will set the target inflation rate and try to manage it. It is often run by the government and less often run by an independent office. Countries will use a non-political central bank often if their political central bank works in lockstep with a leader that prints free money around election times. In the US our central bank is normally called “The Fed” or “Federal Reserve”.

The primary tools the Central Banks have are: 1) to set the monetary policy - do we print more money or borrow more funds and 2) to set the interest rates in a country. For example, the US interest rate right now is 5.5%. This is the rate at which banks can borrow money from The Fed.

Is Inflation Bad?

Depends.

Inflation can be a driver of the economy at lower rates. This is why most country economies strive to keep a reasonable inflation target, normally set at 2% - 3%. This allows for planning for both companies and people. Is this the correct target? It has worked in the past, so this is what economists take to the future. The consensus before Covid was that this was the right target range. Going forward this might change - the US Fed is looking at that issue now because 3% or more looks like it might be viable.

How can a country proactively influence the inflation rate? Central banks do this by limiting or expanding the money supply. When inflation is running too high, the central bank can increase the interest rates it charges to banks, which then pass this on to consumers. By charging banks more interest they have to pay, the banks raise the interest rates on businesses and consumers. This will cause the economy to slow down, although it almost always drives unemployment up. As a company must pay more for their purchases, they often lay people off (fire them) to be profitable.

When inflation is too low, a country might make money more affordable by lowering interest rates, or by printing more money. During the first parts of Covid, some banks in Europe were charging “negative interest”. That means that if you borrowed $1.00, you would owe $0.95 new year. the desire with this is to push money out to the people via banks. The other thing that can occur and did occur during COVID-19 is something called “Quantitative Easing.” This increases the money in the economy by issuing new funds to the government which then buys securities from the market. Money flows out into the economy to try and increase business and inflation.

Why Higher Unemployment Doesn’t Stop a Central Bank from Raising Rates

Since Ronald Reagan’s two presidential terms, the US Central Bank has employed high rates to lower inflation and keep it low. The typical complaint is that this method will drive unemployment. Here is the honest admission about this, the Fed cares more about the economy overall than people. The Fed will officially say that more competitive businesses will end up hiring more people in the low run. So The Fed trades short-term help for companies at the expense of consumers. You could say that this is an economic trade-off that experts agree on. Unemployed people would disagree.

Hyperinflation

One of the main reasons central banks will hobble economies in order to control inflation is the history of hyperinflation. Hyperinflation is technically when interest rates rise over 50% in 6 months. So imagine our first example that instead of $102 at the end of the year, our $100 basket of goods would cost $225 if the inflation rate was 50% per month. A country might then print more money, which makes the current money worth less and less.

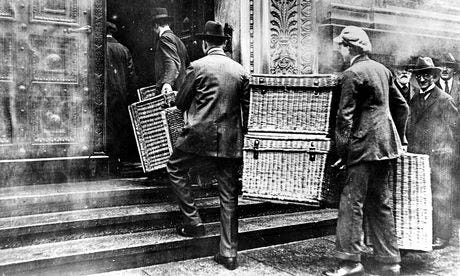

The most common example of hyperinflation occurred in the German Weimar Republic. In the 1920s Germany depended on American loans. When the world went into a depression in the 1930s, Germany could not afford to pay back these loans. Moreover, Germany was required to pay massive reparations AND had to give up industrial areas after World War I. The demands of these payouts put pressure on German Banks, which raised interest rates. The central bank addressed this by printing money. The more printed the less it was worth.

At the beginning of 1920, 50 marks were equivalent to one US dollar. By the end of 1923, one US dollar was equal to 4,200,000,000,000 marks. That is 4 trillion marks to a dollar.

A more recent example is Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe started in 1980 as a successful African country after a long history of colonization and then apartheid. The government was created with both Black and White settlers. But starting in the late 1990s the government instituted land reform which consisted of appropriating land from the white Zimbabweans to give to the Black population, particularly those with government connections. Zimbabwe was also backing a war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Zaire).

The war was a drain on resources that could not be financed. The land reform gave much of the land (and later the businesses) to the people who were not taught to farm or run businesses. The economy tanked, and the government printed money to pay expenses. Printing money that is not backed up by productivity crashes the value of money.

This is what happened. Using simplified numbers, let’s take an example. Say a loaf of bread costs Z$ 10. Inflation in 2001 was 55% so that bread would cost Z$ 15.50 a year later. Then the inflation went nuts. In 2007 prices shot up at a yearly rate of 662,000% So a loaf of bread that was Z$10 in 2006, would cost Z$ 6.6 Million. It got worse in the following 2 years. In the case of Zimbabwe, the locals choose to turn their money into US dollars, South African Rand, or any other currency that holds its value. The government responded by outlawing the use of anything except Zimbabwe dollars, which only made it all worse.

The hyperinflation only stopped when Zimbabwe started using US Dollars instead of local money. Because the supply is limited and not controlled by political actors, the US dollar stayed relatively stable in inflation. The economy and money supply stayed relatively stable until 2019. In 2019 Zimbabwe introduced a new currency that was at parity with the dollar. But since Zimbabwe can print its own money again, inflation started up again, now at 191% - remember our target is 2%. When this new currency was introduced it was valued at Z$1.00 to US$ 1.00 – on Aug 14, 2023, the official rate is Z$ 322.00 to US$1.00.

Deflation

Deflation is when the cost of goods decreases year over year. If it continues too long, it leads to high unemployment. Deflation indicates to consumers that prices year over year will fall. If it is one or two sectors, like energy or cable TV rates, this is not usually what we mean when we talk about deflation. For example, in the first year of Covid lockdowns, oil prices dropped to near zero. This was due to a lack of demand and a glut of oil. But disposable income rose and there was no full deflation or the effects. In a situation like this, where a short-term fall in prices can easily be explained, that is not deflation.

The most often quoted example of deflation happened in Japan starting in the mid-1990s. I will say there is not a consensus on what drove Japan’s deflation completely, but there is a great paper that explains it more fully. I will try to explain it in laymen terms.

In the 1980s and 90s, Japan had a huge excess of liquid funds. The value of buildings, houses, and land prices grew rapidly from the late 1980s. The Yen was very highly valued (later it was seen as very overvalued) and banks were eager to lend. The Japanese traditions included high levels of savings, which could be used with the high value of the Yen to invest in the United States. Japanese investments in the United States ran as high as $16.5 Billion in US properties alone. The Japanese purchased businesses and icons (like Universal Studios and the Chrysler Building) which prompted outrage by US interests.

The reckoning gave in later in the 1990s. There was a recession1 and the property bubble burst. The value of the building stock plunged. And the repayment to the United States was priced in dollars. When the costs of repayment rose due to the rise of the US dollar, servicing those loans was more difficult. The recession in Japan lowered the value of the yen. This meant not only was the economy slowing, but that the cost of dollars to pay loans went up as the yen fell. (Example: when a loan was made for $1,000 and had to be paid back when the yen was US$1 = JPY 10, it would cost JPY 10,000 to pay back that $1,000. But when the Yen drops to US$1 - JPY 7.5, then the cost to repay a $1,000 loan is JPY 13,333).

Dropping home prices and the drop in bank wealth slowed the economy down a lot. The bubble and loss of savings affected the Japanese household as well. Japanese responded by saving more money – to replace the value they lost.

By saving more money, there was less money used to purchase consumer goods. Therefore the prices of consumer and business goods dropped – less money chasing more goods. The country responded (and has continued to respond) with extremely low-interest rates, including negative interest for a while. They were trying to drive more spending to escape the cycle of saving and not spending. Spending would raise inflation, but the previous crash limited the desire of people to spend. Since many people were burned in the 1980s, the population banked extra funds. The Central Bank equivalent in Japan has not been able to resurrect inflation to repair the economy. Its economic growth year over year in the aggregate fell from the 1980s – 2008. Since then, the economic growth rate has fluctuated between 0 and 2%.

Interestingly, China has also experienced the twin effects of the real estate bubble and increased savings (hence less money available for purchases). China is trying to catch this early and learn from Japanese experiences. It is unclear if this will work.

Stagflation

This was considered a near-impossible situation until the oil crisis of the 1970s. It has only occurred a few times since. Stagflation is when we have high inflation and high unemployment.

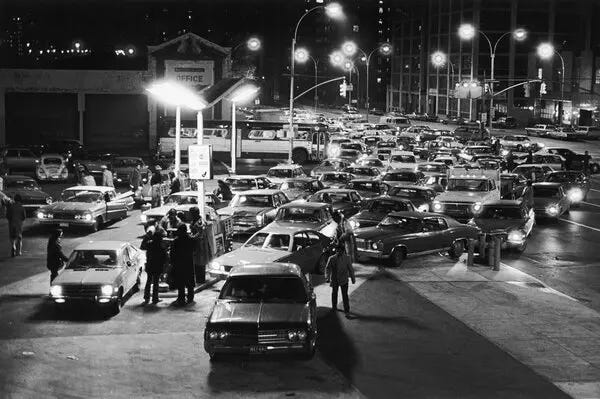

This occurred in the United States after the oil crisis in the 1970s. The inflation rate was already high in the United States and the unemployment rate was flat. Then an oil boycott was implemented by the oil-supplying countries. This spiked inflation as energy costs skyrocketed. However, inflation did not promote economic growth because the economy was hobbled because the United States depended on imported oil. Note: The issue of wild swings in oil prices is still what drives the desire for energy independence.

This situation is very unusual as when there is high unemployment, the demand for goods, and thus inflation, is very low. In fact, the accepted way of fighting inflation is to raise interest rates which will raise unemployment.

This leads to the biggest problem with Stagflation, you have almost no tools to address stagflation. In 1971, the Federal Reserve under Richard Nixon froze US workers’ salaries and put in price controls. This worked a bit, and the situation improved after a drop in the price of oil and an increase in the number of unemployed.

But inflation came back within a decade, and unemployment was rising. Paul Volker, the Fed Chair appointed by Jimmy Carter and most influential under Ronald Reagan attacked inflation with a 21% interest rate. Just to compare that to our current “very high” interest rate of 5.5%. It worked, but was so painful governments have been quick to attack interest rates since then, despite the impact on unemployment.

The Sweet Spot for Inflation and Why?

The United States’ target for inflation is 2%. Most of the developed economies shoot for interest rates at about that level. That number allows for year-over-year price and wage rates to grow at a predictable and tolerable rate. We find that, in reality, a 2% year-over-year wage increase for all workers does not happen. We tend to grow the economy more than we do wages in the United States, concentrating more wealth growth for the richest of us, not the poorer.

But a question arises, Why should we have inflation at all?

Inflation is naturally created when the productivity of each worker grows, without a close match in wage growth. Say that as a manager you used to have a secretarial pool for the company to write memos, letters, and business mail. You also had a secretary to set up flights and hotels and get the physical paper or copies of information you need. You may need a separate stenographer to “take your letters” as well as typing them up. The output of the secretarial pool has to be checked, so you have a manager who checks the grammar and spelling before the letter is sent back to you to check.

Now we have computers that do all of that. The output of that 1 manager and 3 assistants all together can now be handled by yourself and perhaps with a part-time secretary. Information doesn’t have to be lugged around in hard copy, it can be on your device. Even if you do a bit less because you’re running to the printer, you are now doing 4 people’s work with only 1 or maybe 2 people. This increase in productivity is what leads to inflation. A similar thing happens when many small farms are purchased and aggregated into one single large farm where economies of scale occur.

We can easily see the downside of this process in the form of less competition and fewer jobs. The economy has to grow fast enough to absorb all the newly unemployed workers.

Why Growth

This question goes to the heart of a new set of challenges in developed countries. Most economic growth is created by people entering the job market. Before the crackdown ionn immigration, much of that growth of workers was created by immigrants. Either coming over to work themselves or having children here at a greater rate than in other nations.

But if a population is steady or falling, how do you keep the economy growing? There are more old people being supported by fewer young people. As we curb immigration the ratio of young to old gets worse. If fewer and fewer employees pay into Social Security, the burden of all those retirees who get Social Security is more at risk.

Seems a dark way to end this, but that’s all folks.

A recession is described as 2 quarters of negative growth in a country’s economy. We as consumers usually sense a recession only if the economy slows down to the point where it affects jobs or housing prices.