Americans are used to the application of the census. The Constitution mandates a national census every 10 years. In other nations, the Census is less frequent or more problematic. Counting everyone in a country seems it would be relatively easy, albeit labor intensive. In fact, it is not easy and did not always include population counts.

Historical

Most historical information is primarily pulled from the Population Reference Bureau.

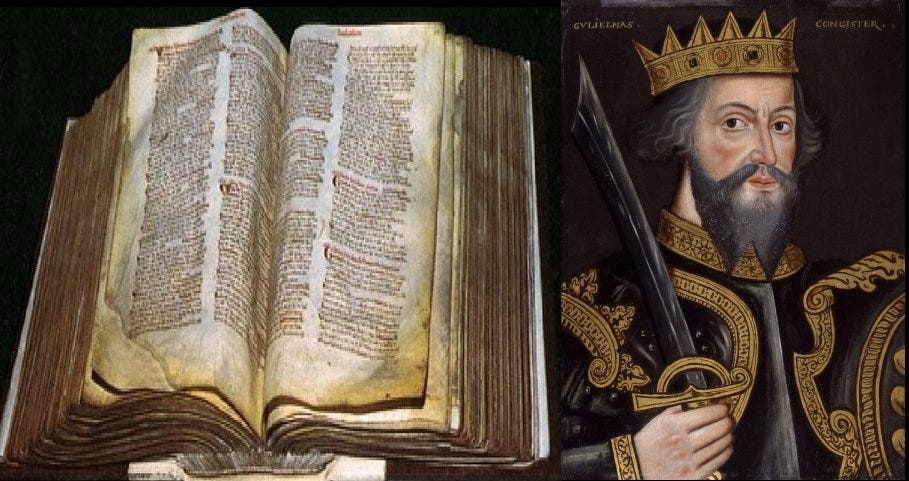

Early censuses were not done to enumerate people like we do today but to take a census of goods for the government/ruler. The earliest census was in 3800 BCE and was used to enumerate livestock, butter, milk, honey, wool, and vegetables. The oldest surviving census is from China’s Han Dynasty in 2 CE. One of the best-known censuses (in the West) is England’s Domesday Book. The ledger of landowners and their holdings was used for tax purposes. A tax identification role that the modern census still provides.

Modern Censuses and Issues

Today, a census is associated mainly with population counts. In some countries, raw numbers are used. In the United States and other countries, names and demographic information are collected to understand cultural and population trends in the country. Since the census in its modern iteration can be used for critical information, there are issues that bad-faith actors can exploit. To understand these problems, you also have to understand the root cause.

Problems associated with legal residents versus illegal and undocumented residents.

In many countries, including the United States, the census is used to apportion political power and economic support for the various states and cities. In the United States, both political parties find fault in the current system concerning undocumented people. Republicans complain that the counting of non-citizens skews the economic support and political support towards cities and those states that have large undocumented populations. Democrats, in turn, follow the axiom that any resident should be counted, and those that which can’t be physically counted should be addressed statistically. They hold this position mainly because undercounts occur in urban areas, where Democratic political power is usually located. Both undocumented and documented populations, primarily Hispanics from Mexico and Latin America, are afraid to fill out census forms because of fear they will be harassed.

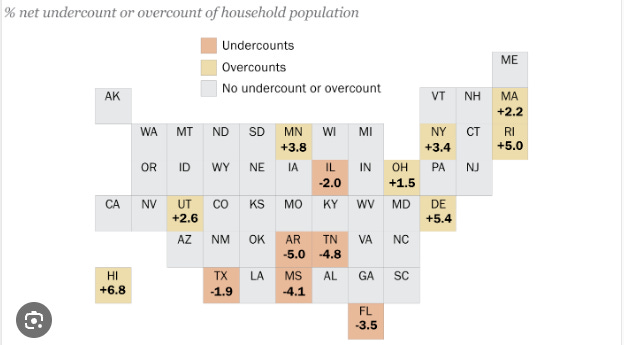

To resolve this issue, the undercounting of undocumented, undercounting of minorities fearing retribution, children, etc., the country has long used statistical estimates based on targeted counts of populations in the area. This is supplemented by supporting ground investigations by census workers. These workers can reassure people that the only count they must give is the number of people in a household. Everything else is voluntary. The census workers can get a more accurate count by reassuring the unwillingness.

The question then is, does this meet the needs of the Constitution, which states clearly in Section 2:

“The actual enumeration shall be made within three years after the first meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent term of ten years, in such manner as they shall by law direct."

In the run-up to the 2020 census, the Trump Administration argued that undocumented aliens should be counted AND identified so that their numbers don’t affect the apportionment of political power. But, by asking people if they are undocumented, the returns would be skewed against states and cities that have significant undocumented populations. Undocumented people will rarely answer with both where they live and their legal status. The argument of who should be counted and how was raised to the courts concerning the meaning of “actual enumeration” and should this enumeration include undocumented non-citizens. The rulings pushed for a total count of all residents, regardless of status.

At the state level, equivalent arguments have been made over prisons. Should prisoners count as people or be pulled out of numbers when determining the population for political reasons? This argument is often had in more rural areas, where a large prison population can change economic allotments. The population count for the city of Dannemora, New York, is more than doubled in size by its prison. Since prisoners cannot vote, this gives the city an overstated weight in local, county, and state government.

Many other countries have this same issue with undocumented residents. In some countries, the number of undocumented are not counted because they are thought to be transient and just passing through the country. For these nations, for example, Jordon, the temporary nature of the Syrian refugee camps means that allocating political power to undocumented people would overwhelm the political system.

In other European countries, the population of undocumented people is overcounted so that the nations either get more EU funds to support them or to justify refusing more asylum seekers.

Problems with Political Assumptions

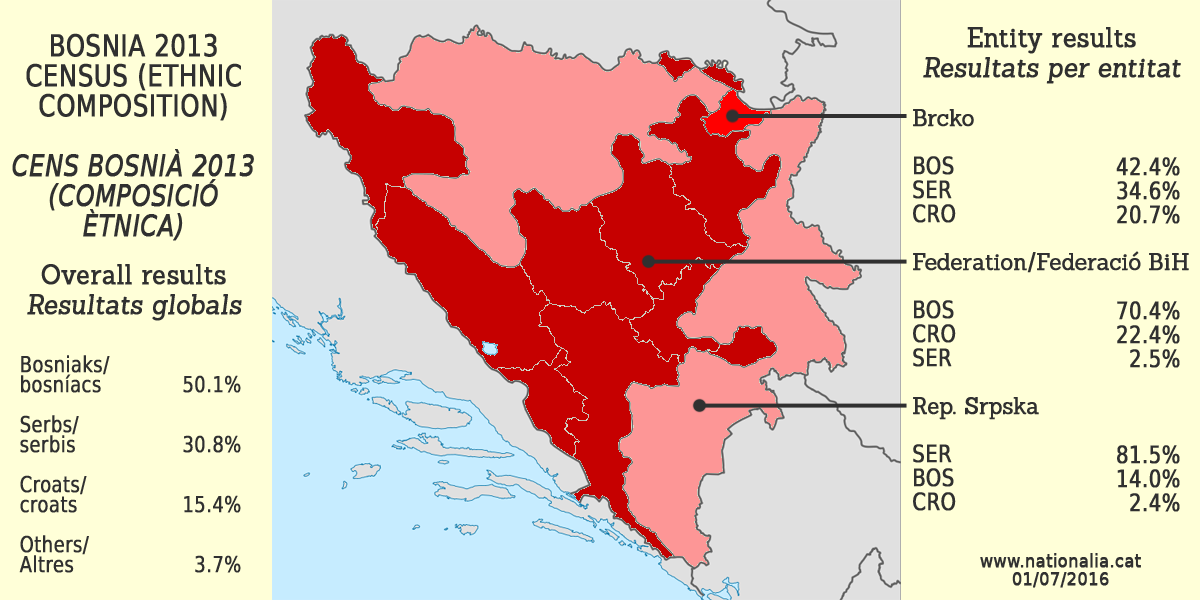

Bosnia and Herzegovina had their first Census since the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991. Since then, taking a census has only happened once, in 2013. The country's political entities argued over how to count in the run-up to the census. In Bosnia, there are three main “ethnic” groups: Bosniaks, Serbians, and Croats. The Bosnian / Serbian war changed the population as a million people fled. None of the ethnic groups were ready to acknowledge changes that might lower their political power.

The 2013 census showed a population drop of ~800,000 people, or 19% of the population. The census showed a relative decline, as a percentage of the population, for Serbians and Croats. The percentage of Bosniaks grew to over 50% of the remaining population. However, the political power is still concentrated in the Serbian population. The changing numbers put pressure on Bosnia to somehow reapportion political power. The changing numbers also put pressure on the Bosnian Serbs to merge their proto-state with Serbia.

For Bosniaks, the changes meant they should have more political power. For their part, the Serbians rejected the census results to preserve the status quo.

Israel has a similar problem. The census of 2022 described the Israel population, but only within certain areas. Israel includes its census of the population the area of Isreal as approved by the United Nations, plus the annexed areas which are not internationally recognized. These areas are: East Jerusalem, the Golan Heights, the settler-occupied areas in the West Bank (the “Steam Zone”), and the area around Jerusalem of those who have Israeli citizenship. This population is ~ 8 million people.

The Israeli census does NOT include the population of the Palestinian areas of the West Bank, which is ~ 2.5 million, even though Israel controls the area. To include all of the West Bank would dilute the power of the Jewish population of Israel as political power is determined by the proportioned of population.

In the news now is the situation in Montenegro. Montenegro was part of Yugoslavia before that country’s break up. After the breakup, Serbia and Montenegro stayed in a confederation until a national vote brought independence. Here are the problems according to Balkan Insight (balkaninsight.com).

Censuses are a sensitive ethnic issue in Montenegro, where roughly 45 per cent of the population identify as Montenegrin, 30 per cent as Serb, 8.6 per cent as Bosniak and 4.5 per cent as Albanian, according to the 2011 headcount.

Ethnic identity and politics have long been hard to separate in the country, meaning that political parties have an essential stake in the outcome of any census.

The opposition alleged that the pro-Serb parties in the government would use the census to increase the percentage of Serbs through political campaigning and institutional pressure. Ethnic Montenegrin, Bosniaks, and Albanians object to a census run by the Serbian minority.

During the last census, in 2011, religious and political leaders appealed to various ethnic and religious groups, urging them to declare their respective ethnicity or religion in the headcount.

Problems with local reporting methodology

India conducts a regular census, but it has become contentious. The current plan is to use a fully digital method through a mobile phone app. This presents problems with the distribution of mobile phones. The poorest people may not have a mobile phone, and any estimate of them may be wildly off, depending on the methodology. A distrust of the government might also reduce the participation of religious and ethnic minorities, granting more power to the currently ruling government. It is a government that many people and foreign nations believe oppresses minorities.

In Indonesia, the census is used to identify the number of households and, therefore, taxes. An undercount is assumed because people want to avoid paying taxes. So the census must be reconfirmed by workers.

In South Africa, the census asks people to self-identify as one of 4 ethnic groups: Black South Africans, White South Africans, Coloured South Africans (mixed race), and Indian/ Asian South Africans. During apartheid, only the last three ethnicities were used to apportion political power and rights.

Niger is an example of a country that finds it very difficult to conduct an accurate census amid unrest and war. A census hasn’t been done in Niger in 10 years. Current civil unrest makes a census challenging to conduct and impossible to confirm. After a civil war or recent coup, rulers will often exaggerate the population that supports them and undercount those populations in opposition. This happens across the globe.

Problems with international methodology

A form of census or other population account is reported to the United Nations. The participating countries may present a “clean” picture using statistical updates. But neither the methods of the census taking nor the method of “adjusting” these numbers are reported. National populations can easily be manipulated if the nation desires. This occurs more often in countries that have opaque and unverified methodologies.

How To Address Discrepancies

Two different population counts are considered “standard.” The first is UN national population counts, which have problems we have identified above.

The second count which considered reliable is the CIA fact-book numbers. The discrepancies between the two are most pronounced in the less developed nations. The CIA doesn’t fully explain its methodology, so comparisons with the UN are difficult.

The table below shows the population estimates of both – UN 2022, CIA 2022, in millions of people:

Algeria UN: 44.9 CIA: 43.6

Iraq UN: 44.5 CIA: 39.7

Afghanistan UN: 41.1 CIA: 37.5

Poland UN: 39.9 CIA: 38.2

Canada UN 38.4 CIA: 37.9

Do Census Numbers Make a Difference?

Internal census counts will continue to make a difference in countries with free elections. Applying proportionality in political and economic support will continue to drive local censuses. However, a national census doesn’t really play a part in international affairs. Countries no longer stack up populations and resources to plan out military power.

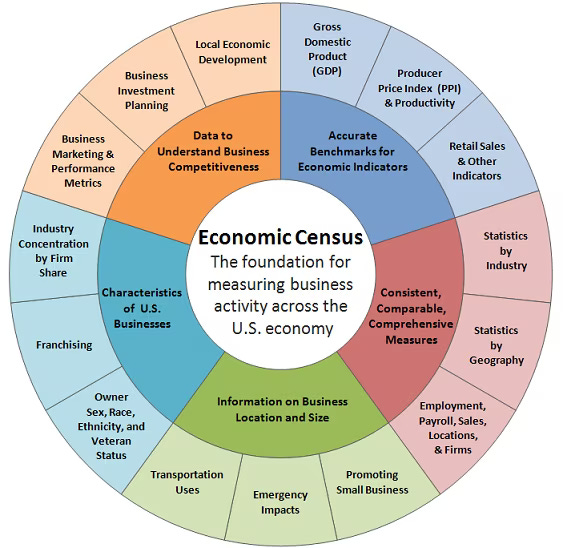

The uses and breath of census numbers may change as statistics and economic development as different development methodologies change. Like those below, the “US Economic Census” numbers may become much more important (from the US Census Bureau.

The methodology will change as the vaccine-implanted chips provide better numbers for use.

(just kidding)