The Cod War

Recent history is rife with conflicts over fisheries; what does this mean in the future?

Technology can have unexpected side effects. One such area is increased efficiency in ships and fishing. We all have imagined memories of fishing, driven by nostalgia. However, the new reality of fishing is very different.

Historically

Traditional fishing was conducted by single fishing boats propelled by oar or sail. They were necessarily small and stayed close to the shore.

Engine-powered boats were introduced in 1866 and quickly employed in the fishing industry, particularly in trawling, which involves ships running far from shore with a giant net dragging behind the ship, indiscriminately catching huge numbers of desired fish and a number of extra species that are disregarded.

In the 1940s, technology (developed for the war) was introduced to fishing fleets. These advances assisted with improved navigation and communications. These innovations continued and included the ability to monitor fishing grounds and to build larger and larger trawlers.

The largest of these, so far, is the Atlantic Dawn. It is 473 feet long, 1.5 as long as a football or soccer field.

With the advent of these large boats and their ability to fish well away from national waters, conflicts over fishing areas were inevitable.

These conflicts have lessons for us to learn today. We must understand past issues to defuse future disputes. The conflicts here are in chronological order.

Background, Maritime Boundaries

Historically

The legal background of maritime boundaries is a recent innovation. Below are the primary laws governing naval boundaries.

In the days of sail and human-propelled boats, there were no laws regarding the fishing rights of nations. Instead, there were local fisheries, often protected by local fishermen against foreign fishing boats. When boats began using engines and could fish far from home, conflicts over fishing rights began to surface.

National limits over the coastlines and fishing beds were often disputed, and there was no rule of law, only the rule of force. This gave rights to different rules over time.

In 1952, the International Court of Justice allowed nations to have exclusive rights over the ocean within about 4 miles of shore. Some welcomed the ruling, but it did not define precisely how far from shore this exclusion zone was.

In 1982, the UN Law of the Sea set up definite limits and rules about territorial powers over the ocean. It provides a 12-mile sea territorial limit and a 200-mile EEZ—Economic Exclusionary Zone. Established freedom-of-navigation rights.

The United States is one of only a few countries that has not signed the Law of the Sea agreement, but it abides by it mainly.

Some Notable Conflicts of fishing rights

Britain - Iceland Cod Wars

From 1958, sporadically through 1976

This conflict concerns Great Britain’s right to fish in Iceland's rich waters. In 1952, after the International Court of Justice upheld the expansion of exclusive rights, Iceland extended its territorial limit to 4 miles offshore.

This limited the British fishing boats’ access to waters they had fished for hundreds of years. The British Navy attempted to force Iceland to allow fishing boats, and Iceland responded. It was primarily a conflict of visuals and light disruption, with nets being cut and standoffs between the navies.

Outcome: The conflict here helped to drive the UN Law of the Sea treaty.

Brazil - France Lobster Wars

1961 - 1963

This was another early fight over local fishing rights between two nations. It concerned France and Brazil because French fleets arrived en masse to fish in Brazilian-claimed waters. Previous to this conflict, France captured hundreds of tons of lobsters in Africa when it had colonies there. As it lost these colonies, it lost the right to fish for lobster, which was extremely popular in France. So, the French took to Brazil to catch lobsters off Brazil’s northeast coast.

Brazil and its fishermen were incensed and began harassing the French fleets and disrupting their actions. The disagreement was based on interpretations of economic rules at sea. Typically, ocean territorial rights ended (at the time) 2 – 12 miles from shore. But in the case of a continental shelf, Brazil claimed the exclusive right to harvest up to the end of the shelf. In Brazil’s case, this was far offshore.

One of the very odd disagreements in fishing arose here. France said that fishing in this area was legal because lobsters swam. Brazil, saying that lobsters only walked, outlawed France from taking these lobsters. The disagree over lobster locomotion was the key differentiator in court case.

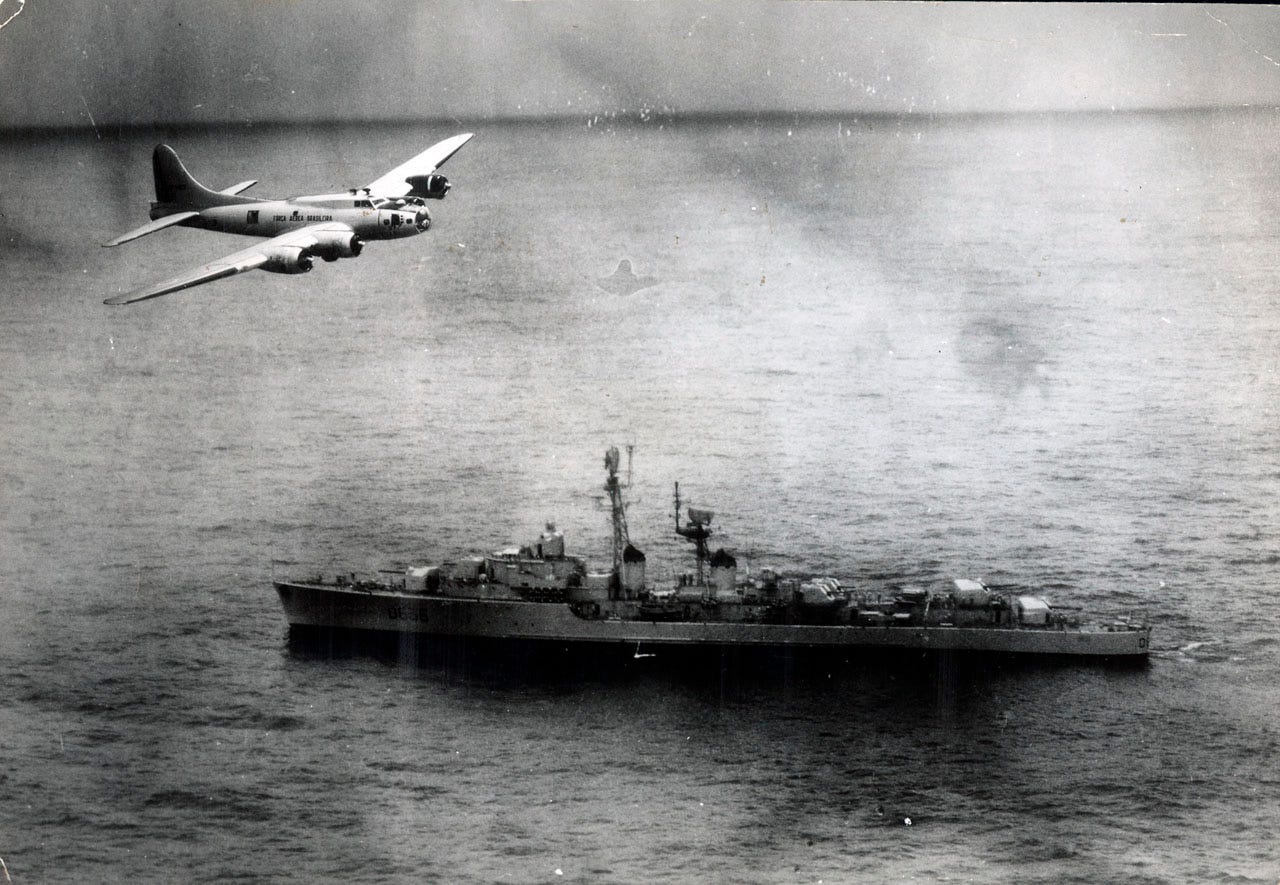

Arguments ensued, and occasional skirmishes occurred because the French government approved licenses in the region, which the Brazilian government claimed was in their exclusive zone. At one point, Brazil sent naval corvettes to the area to drive off French fishing boats. France responded by sending a destroyer to the area. Brazil and France squared off for a naval battle. Brazil mobilized for action with both the Navy and Air Force.

At that point, the US weighed in, saying that the B-17s of the Brazilian Air Force from the US were not allowed to be used against opponents [1]

Outcome: Ultimately, the US and the UN forced the two nations into negotiations. The French Navy left. The outcome was the area WAS defined as Brazil’s territory. An agreement was reached allowing the fishing of lobsters by French ships in limited quantities and time, sharing the profits. Finally, the conflict of interest was resolved through diplomatic means.

Canada – US Pacific Salmon War

1994 – 1999

From 1982 to 1994, an international treaty dealt with the Salmon catch in the Pacific Northwest area of Alaska, British Columbia, and Washington State. There had been growing problems with the salmon fleets of both countries fishing in the other’s territorial waters. In 1982, a treaty was agreed to that stipulated catch limits, open fisheries, and some limited profit sharing.

The treaty ended in 1994, and the US and Canada could not agree on a new one. In the subsequent years, both sides filed lawsuits, and the anger ran very high. Finally, in 1997, things came to a head. Alaskan fishermen were granted free rein for 56 hours to Noyes Island – open to all fishermen later. A Canadian flotilla surrounded an Alaskan ferry in Canadian waters. Negotiations between the two nations continued with more urgency and were mainly concluded by 1999.

Outcome: In 2001, a new agreement was signed, ending tensions and lawsuits.

Cod Fisheries Collapse in Canada and the United States

1999

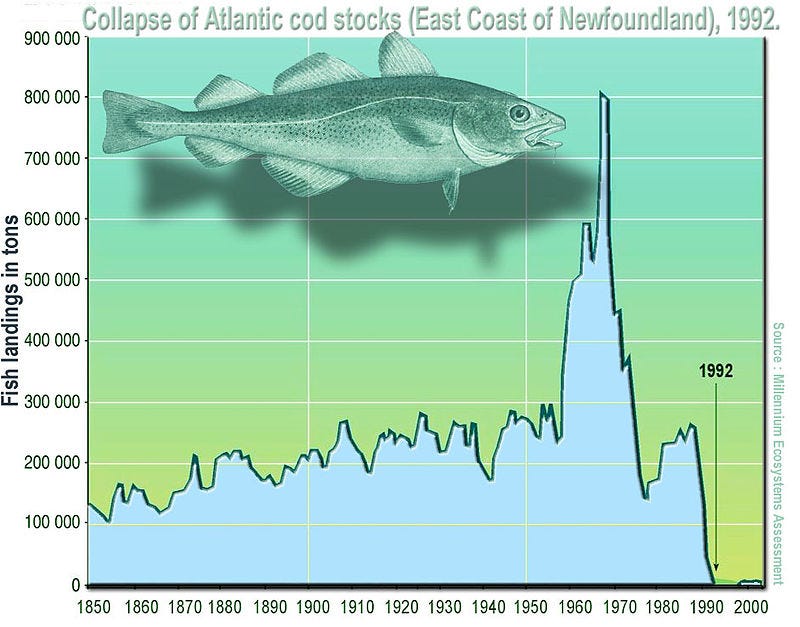

Overfishing of cod, an important fish, caused a collapse of the cod population. Wikipedia has a great summary here:

In 1992, Northern Cod populations fell to 1% of historical levels, due in large part to decades of overfishing. The Canadian Federal Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, John Crosbie, declared a moratorium on the Northern Cod fishery, which for the preceding 500 years had primarily shaped the lives and communities of Canada's eastern coast. A significant factor contributing to the depletion of the cod stocks off Newfoundland's shores was the introduction of equipment and technology that increased landed fish volume. From the 1950s onwards, new technology allowed fishers to trawl a larger area, fish more in-depth, and for a longer time. By the 1960s, powerful trawlers equipped with radar, electronic navigation systems, and sonar allowed crews to pursue fish with unparalleled success, and Canadian catches peaked in the late-1970s and early-1980s. Cod stocks were depleted at a faster rate than could be replenished.

The trawlers also caught enormous amounts of non-commercial fish, which were economically unimportant but very important ecologically. This incidental catch undermined the stability of the ecosystem by depleting stocks of important predator and prey species.

But in 2002, after a 10-year ban on fishing, the cod population still had not (and still has not) recovered. This has been blamed on overfishing in the areas it is still allowed. Scientists also theorize the most healthy fish were caught, leaving ocean stocks with poor genetics and hampering repopulation.

In 2015, estimates of the bounce back of cod populations were overhyped, and fishing restarted. In just a few years, the cod populations plummeted, and in 2018, the federal governments of both Canada and the US reduced the cod quota greatly.

Outcome: A moratorium on cod fishing continues. The current situation is rendered more venerable because the rise in ocean temperature in the area reduces cod stock and recovery processes.

Whale Wars

1960s – 1986

Hunting whales has a long history. Before electricity and technological breakthroughs, whale oil lit homes and streets. When the Industrial Revolution introduced machinery worldwide, whale oil was used as a lubricant because it held up in cold weather. In World War I, the armies used it in many ways. Between World Wars I and II, better substitutes were invented, and electricity provided the energy for lighting and heating homes. Whale hunting became unimportant for most countries.

In the late 1960s, movements to stop whaling gained strength. In 1970 and 1973, the United States declared different versions of whales endangered. Attitudes were even more strongly anti-whaling in Great Britain. In 1960, Britain ended whaling, and in 1973, Great Britain outlawed the importation of whale products.

From 1986 through 1990, moratoriums banning whaling by species were adopted by most of the world’s nations. Whaling is now illegal internationally, although Iceland, Japan, and Norway continue their activities at much-reduced levels.

The “Whaling Wars” refer to the action of Greenpeace against whaling vessels. They harassed whaling fleets from 1972 through the ban on commercial whale hunting in 1986. Sporadic demonstrations have occurred since, but as whaling ended for the most part, the associated Greenpeace movement basically ended.

Outcome: Whaling was outlawed in stages from 1986 - 1990. Whale populations have slowly recovered.

Other notable examples

Several other conflicts have occurred over time, many of which have continued to the present.

2000s: Lobster Conflict Canada / Native Americans / US

Current: French / Jersey Island ongoing Fishing dispute

Current: Chinese South China Seas Fishing Boats

Current: Overfishing due to seabed trawling.

There is also a conflict in the South China Sea that is less about fishing and more about maintaining the Chinese territorial claim with a hybrid fishing/armed fleet.

Lessons Learned

These incidents illustrate that there are three reasons for conflict over fishing rights. (Note: I understand whales are not technically fish, but we will temporarily define them as such for this article).

Managing fishing and fishery health in international areas between two or more countries.

Managing fishing and fishery health in international waters between national fishing fleets and ecological demonstrators.

Managing fishery health in the face of overfishing and collapse of species

Future of Fishing and Expected Issues

Over a billion people rely on fishing as a primary protein source. More people in rich countries eat fish occasionally, but focusing on some fish, such as salmon, means overfishing or farming of these types.

Climate change will affect fishing in two ways.

- The rise in ocean temperature has an unexpected influence on fish stocks. As of now, we are not sure how much the temperature will rise in different fisheries. Since cold water can support more ocean life than warm water, the effects will typically lower fish populations and catch yields. We can expect more conflict between national fishing fleets in international waters.

- Fish population collapse. As demonstrated by the cod and herring fisheries, overfishing can decimate a fish population in certain areas. Depending on the species, the population may or may not rebound. If this collapse triggers a collapse in the other species in the oceanic food change, instability may occur in ways we do not understand.

The result is that overfishing, which is occurring now, may cause a further drop in yields that will endanger the health of people dependent on fish protein. Subsistence fishing yields have already dropped, making more people dependent on commercial fishing and draining some species' open sea populations.

It seems likely that climate change will reduce crop yields on land and fish yields in the ocean. Conflicts between nations affected by climate change will increase. It will add a lot of pressure on international conflicts that will only increase.

Fish farming may replace ocean-caught fish in wealthy nations, but this will not help poorer countries. We can expect minor skirmishes over fisheries to continue and grow over time. The most powerful nations will be able to impose unilateral decisions.