The Range Wars, including the Fence War and Sheep War, were not “wars” in any typical sense. The conflicts occurred between settlers and ranchers in the American West. They were fought over private and public land, access, and grazing rights.

In America, the image of the Wild West has been iconic for over a century. Over time, we have learned that many of our ideas about the “Wild West” were wrong and driven by Hollywood, not history: guns were not prevalent in cities, public shootouts were very rare, and the Native Americans didn’t attack Wagon Trains – they mainly traded with them. In contrast, the Range Wars and associated conflicts were real, but they rarely met our cinematic ideas of how the “West Was Won.”

Contributing Factors

Land

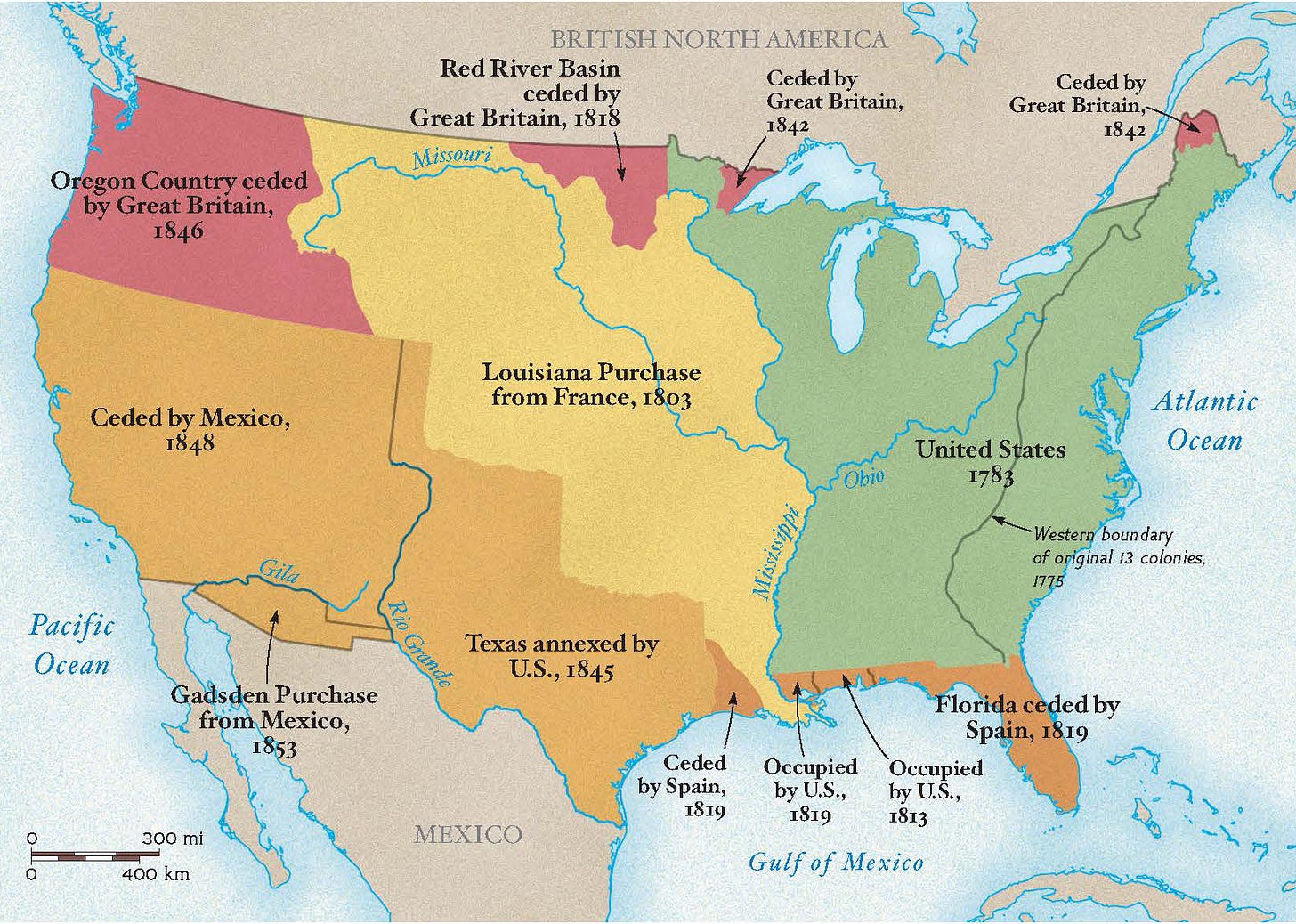

The first new area acquired by the US was the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. It opened the Great Plains, where farmers settled. The next big chunk of land was farther west. At the end of 1845, the area of Texas joined the United States. The addition of Texas and the territorial gains from the Mexican-American War of 1848 opened vast tracts of land.

Suddenly, the United States had possession of the land to the Pacific Ocean. However, populating this area was not an easy task. First, the Native Americans had to be pushed out. Second, there had to be some reason for Americans to move west. Much of the land up to California was not productive for farming and was wide open to pressure from the Native Americans, Mexicans, Mormons, and more. The US government wanted to enshrine its claims and settle people in these empty areas. The Civil War from 1860 to 1865 put a hold on expansion, but it quickly started again after the war was over.

The Railroads

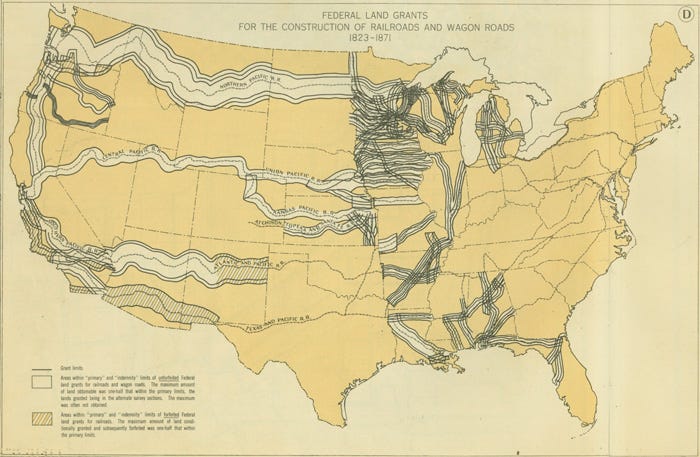

The railroad opened a corridor from St. Louis to California in 1869. The railroad owners convinced the government to grant land along the tracks for infrastructure and to sell to farmers, rangers, and new city residents. The land was given to the railroads as a further incentive to complete access to the nation. In itself, it doesn’t seem like that should cause any problems, but the land granted to railroads was equal in area to the state of Texas — a massive amount of land.

The railroads also opened up the ability to transport cattle to markets in the East. The great cattle drives occurred from south and west Texas up to the trail route. The railroads opened movement to cities and regions previously unserved, increasing land value in the western US.

Residents

The first non-Native people who worked and lived out West were cowboys and cattlemen. As some cattlemen got rich, they bought other ranches and land and expanded their herds. This led to a subset of cattlemen who were very rich, very territorial, and politically connected.

The net wave of economic migrants was sheepmen, who began to settle and graze their livestock in the west. Sheep grazed the same lands as cattle, and there was near-constant tension between the two.

Finally, as far as this posting is concerned, farmers were lured by free land and easy railroad access to markets.

The Homestead Act of 1862

Under this law, the government offered 160 acres (65 hectares) to people willing to reside on and improve the land. Farmers (and sheep ranchers) took advantage of this law to settle much of the West. This program took land from the public domain and gave it to individuals. Previously, the public lands were often used for cattle stock grazing. The Homestead Act took much of this public land and turned it private.

Cause of Conflicts

The Sheep War

As sheep ranching spread west, cattlemen and sheepmen clashed over grazing on public land. The sheep decimated grazing lands per cattlemen, making them unfit for cattle. Cattlemen had been in most areas long before sheep got there. One of their first responses was to fence off private AND public lands for their herds. The two also clashed over water rights, grazing rights, and cattle ownership.

Because of long-standing relationships and donations, cattlemen had much better political connections to local and state governments.

An example of this cozy relationship can be found in ruling about “sheep scab” (mange). Cattlemen claimed that sheep scab was prevalent and threatened their cattle with scant evidence. Texas passed laws that required every sheep to be inspected for the disease, long before there were enough inspectors and ways to prove inspections had been conducted. Other state laws were passed that prohibited sheep from grazing on public lands but exempted cattle from this requirement; laws prohibited sheep herds from crossing county boundaries and denied them the right to cross private land to reach public lands.

This led to cattlemen killing sheep ranchers and their sheep in Texas, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, and lesser conflicts in other states.

These conflicts continued until a 1909 trial that convicted ten men of murdering sheep ranchers. The killers were hired by a wealthy cattle owner, who was now on the wrong side of the law and public opinion.

The Fence Cutting Wars

The conflict between the men who raised cattle versus sheep resulted in the fencing of great swathes of land to keep sheep out. Barbed wire fences were used after their creation in 1887, exacerbating the conflict. Fencing increased as farmers and settlers moved into the western US. But the cattlemen, long the protected class, fenced more than just their land. They fenced public land to claim exclusive access to that land. The fences also took in farmland, which hadn’t yet been planted. The public land that was fenced often prevented access to other parts of public land so that no one else could use it.

This caused the “Fencing Wars” during and after the “Sheep Wars.” Farmers, and to a lesser extent, sheep ranchers, would cut fences on public land or land that prevented access to public lands.

An excellent summary is found in Wikipedia:

Fence cutting soon erupted as a result of the cattlemen with vast lands using barbed wire to fence their land, cutting off roads and access to public lands. The cuttings were well organized, with armed guards posted to protect the men while they worked.[12] In 1883, fence cutting was reported in more than half the counties in Texas.[13] To stop the fence-cutters, the state and local authorities tried many different methods. Counties offering rewards, shootouts between landowners and fence cutters, and legal trials were all different ways in which people tried to stop the fence cutters, but the conflict persisted.[14] The fence cutters had substantial local support, and on occasion, found powerful outside allies. For instance, the New York and Texas Land Company was making profits by selling their land to homesteaders, and hence supported fence-cutting campaigns against the cattlemen.[15] Local newspapers lined up either for or against the fence cutters

After impacting economic growth, many states outlawed fence cutting and pasture burning.

End of the Range Wars?

The Range Wars ended in the early 1900s. Economic growth from farmers and settlers swayed politicians to crack down on the illegal activities of all participants.

However, legal and illegal confrontations in the West haven’t completely disappeared. For example, in 2014, after 21 years of requests to Cliven Bundy to pay for grazing on public land, a stand-off ensued. Bundy refused to pay the Bureau of Land Management for grazing AND refused to leave public land, daring the government to act.

The BLM decided to prevent Bundy from moving his cattle back from public land. The local sheriff rounded up Bundy’s livestock and then arrested the men who refused to leave public land in Nevada. This resulted in an armed standoff between law enforcement and Bundy’s supporters. Ultimately, negotiations occurred between Bundy, the local sheriff, and the new BLM director. The BLM director decided to de-escalate the situation and pulled back. Bundy continued to graze his cattle on public land, not pay for it.

A contributing factor in this was Bundy’s view of Black Americans in general and specifically against the first Black President, Obama. There was widespread pushback against government policies if they occurred during Obama’s Presidency. Here is what Bundy said one week after the confrontation:

I want to tell you one more thing I know about the Negro. When I go to Las Vegas, north Las Vegas, and I would see these little Government houses, and in front of that Government house the door was usually open, and the older people and the kids and there was always at least half a dozen people on the porch. They didn't have nothing to do, they didn't have nothing for the kids to do, they didn't have nothing for the young girls to do. They were basically on government subsidy, so now what do they do? They abort their young children, they put their young men in jail, because they never learned how to pick cotton. And I've often wondered, are they better off as slaves, picking cotton and having a family life and doing things, or are they better off under government subsidy? They didn't get no more freedom. They got less freedom.

Today and in the Future

The current iteration of range wars is more about environmental and ecological preservation. The cattleman’s viewpoint is well summarized by the TV show Yellowstone, which shows the ranchers' devotion to open land and public grazing. Public interest groups or Native American tribes are now the initiators of anti-grazing lawsuits.

I think this will change in the future. Climate change will eventually force a reevaluation of the US public lands policy. The relentless advance of urbanization into the West is causing problems as people escape expensive housing and overpopulation only to find that their very movement into these lands brings the issues they are trying to avoid.

The old “range wars” have morphed into legal conflicts, preferable but constant.

UPDATE

I wrote about the impact of Ocean Temperature Rise a few weeks ago. The New York Times just printed an article and temperature graph about this year’s records. The ARTICLE is here.