Note: I am from Los Angeles and LOVE the city. But you have to be honest about the good and the bad. PS: The good – perfect weather 90% of the time.

Los Angeles is dry metropolis in a thirsty state. But the planners of the city very early realized they needed a secure source of water; one they owned. Los Angeles realized they had outgrown their water supply by 1902. Without water the city, industry and agriculture could not continue to grow. And so one of the fastest growing areas int eh country needed water due to its geography.

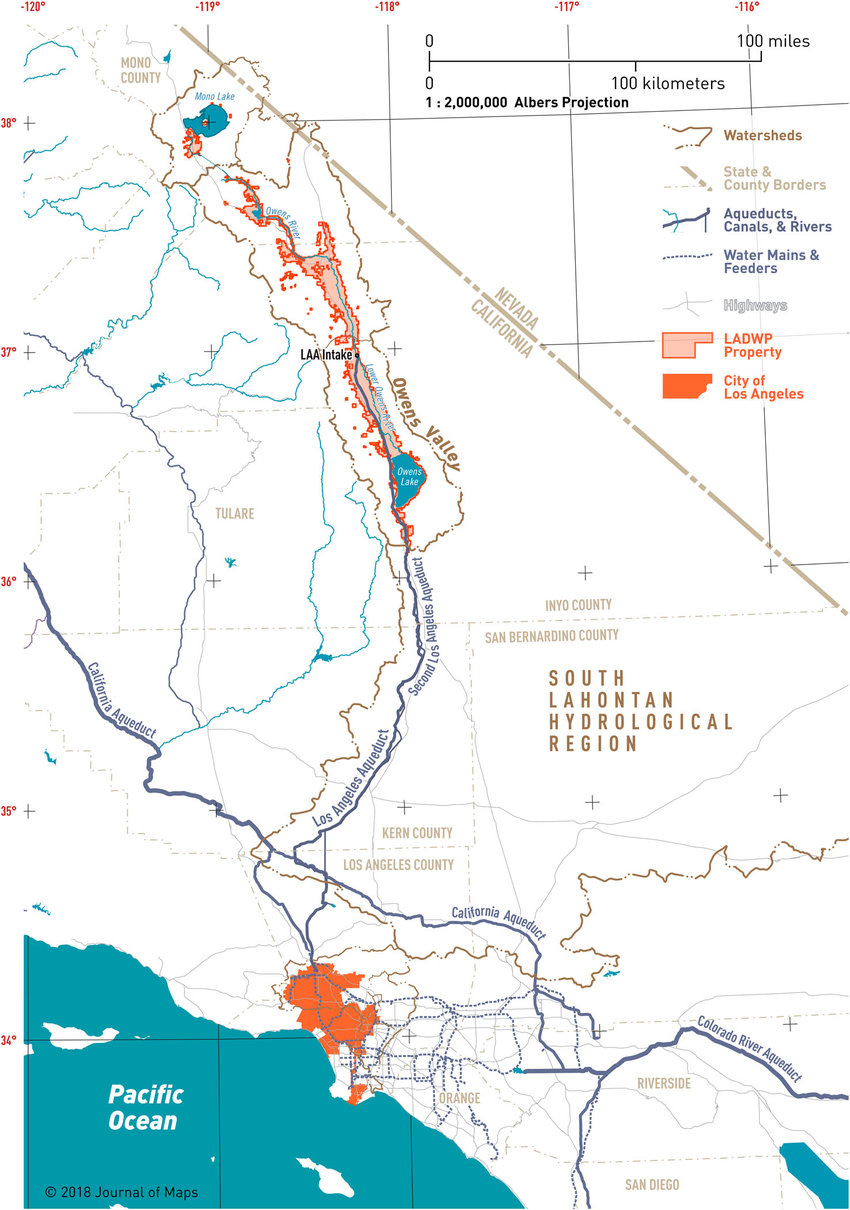

To address the issue, city planners decided to create a new project to being water to Los Angeles. By 1913 the first Los Angeles Aqueduct was completed by Willian Mulholland (if you’re from LA, this is a big name). So how did they do this?

The Purchase and Use of Water Rights

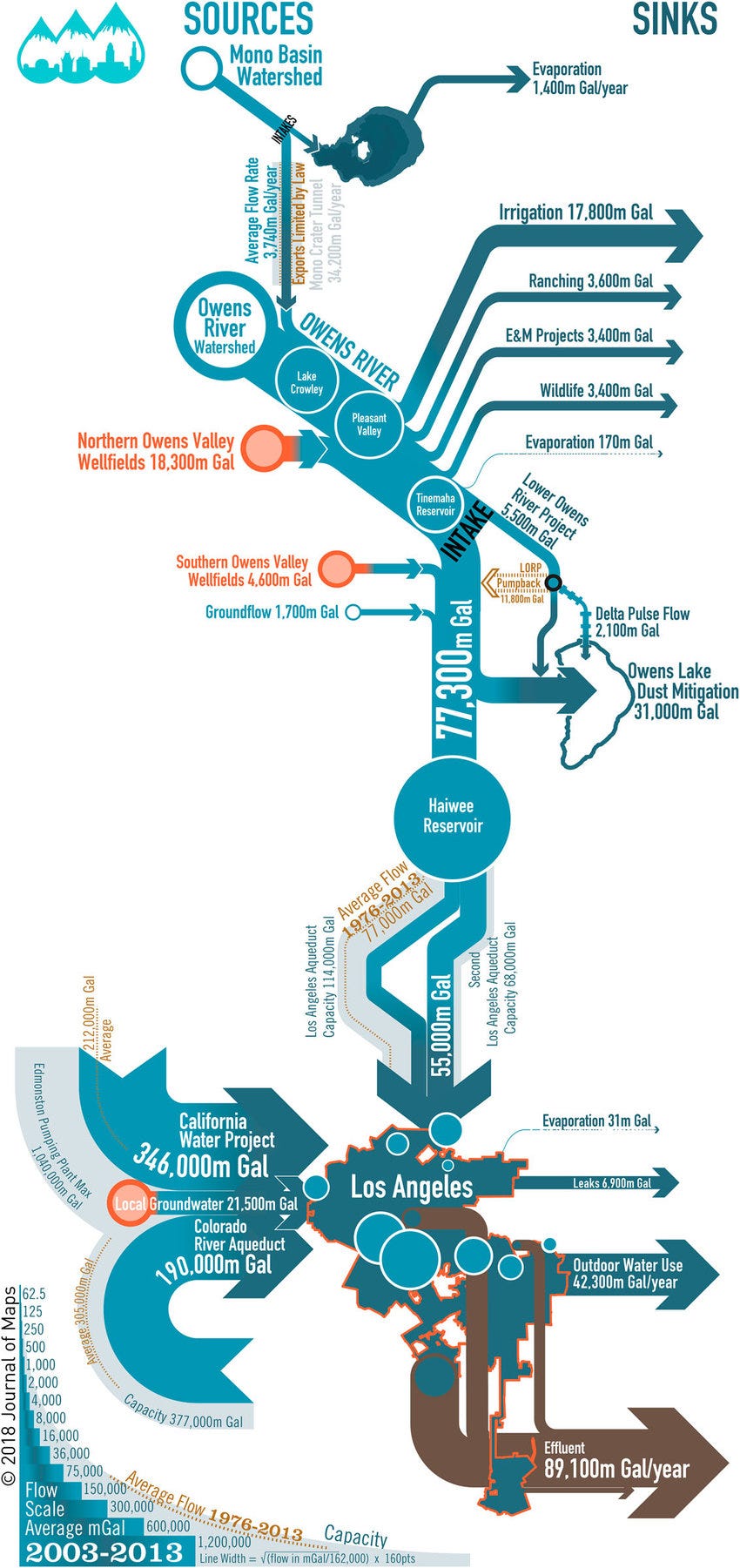

One of the first thing Mulholland did was to by the water rights of the Owens Valley. The city also purchases land on the east side of the Sierra Nevada mountains. The run off from the west (and wetter side) was already claimed by the Central Valley and San Francisco. The proposal promised by the c ity was that Los Angeles would only take excess water This was a lie.

He also undersold the pure amount of water that would be diverted, drying up Owens Lake by 1924.

Because the city of Los Angeles was legally limited to supplying water only to the city, Los Angeles grew to the second largest city in area (at the time). Some neighborhoods and cities joined to get water for their residents. One of the biggest prizes was the agriculturally rich San Fernando Valley, which was annexed. The San Fernando Valley, now vast suburban tracks, was originally farmland. The water from the aqueduct was delivered to the San Fernando Valley and refill its aquifers. The water changed the farmed crops from wheat to water dependent crops like citrus – oranges, apricots, lemons, and persimmons.

An Aside – Energy

Oddly for a project like this, the Los Angeles Aqueduct created energy. The various catchment areas in the mountains not only held water but created power as the water flowed down. This is why the name of the organization is The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

Interestingly, when the energy crisis hit – think of Enron – the city of Los Angeles residents did not have to pay extra for energy. Most of it was obtained from the Aqueduct, and yes, some of the energy was from coal fired plants in Utah – but we try not to talk about that.

The Colorado River Aqueducts

Los Angeles knew that additional water sources had to be discovered

Los Angeles paid a large part of the funds to build the Colorado Aqueduct along with the newly created “Metropolitan Water District.” The MWD was a consortium of Los Angeles, Orange County and San Diego county area, but not Los Angeles city. The city of Los Angeles paid a major portion of the construction cost - along with the Depression era public works campaigns. The reasoning was that if there was a problem with Los Angeles’ water supply, they had a claim to the Colorado River.

The Colorado River aqueduct also supplies the majority of San Diego’s water supply through a diversion in the desert.

Future

There are too many people and too little water in the American Southwest. This has now caused major problems now with the Colorado River Compact. The compact was signed in the 1930s and sets the terms for the water allotments. California was allotted 59% of the lower basin water (about equal to the upper basin supply). Arizona was granted 37% and Nevada 7%.

California was also allowed any extra water not used by other states. And it took that excess water until the 1990s.

In the mid-1960s Arizona built Central Arizona Project, in order to claim and use its portion of the river water. Because Arizona was sparely populated when the compact was signed there were not municipal uses for that water. When the Central Arizona Project was built most of its water went to irrigated farming. As the state grew after the 1960s, less and less water is available for irrigation, causing problems for Arizona farmers. Now the state must contend with competing claims from the cities like Phoenix and the farming lobby.

Water is limited by the geography and climate change is making supply even worse. Snowfall levels are plummeting (2023 is a rare exception) and the demands from cities grow ever larger.

To address this imbalance, more and more cities are requiring mandatory conservation. Many now allow Xeriscape yards or actively outlaw watering existing lawns. However, conservation can only help so much. Today a lot of water is wasted despite many cities’ inducements for conservation.

Meanwhile the economic viability of the area is very water dependent. Farming is still very important not only to California, but the nation. California produces 33% of all vegetables and 12.5% of all agriculture production in the United States.

One of the keys to conserving water, particular in California and Arizona, is to switch to less dependent water crops. Cotton and rice are both heavily dependent on imported water and can pretty easily be swapped out for less water expensive crops.

Almond farmers, avocado growers and many citrus farmers have started to use drip irrigation to their trees. Drip irrigation can lower water requirements by up to 60% AND increase crop yields by up to 90% versus conventional irrigation.

Desalination plans have been proposed, but price to supply ration renders this too expensive – at this moment.

So for now, smart conservation is the key.