As noted last week in Part 1 in the geography overview, the drivers of World War I are generally simplistic, at least in the United States. We know the basics of how the war started, but here, I would like to examine the causes of the war from an economic viewpoint.

The economy and geography-driven economic issues drove levels of antagonism between European nations that ultimately led to WWI. This did not arise in a vacuum. This post will attempt to explain some of the economic causes of the war.

The Economic Landscape before WWI

There were a few main characteristics of world economics before World War I that exacerbated international tensions.

World Trade and the Industrial Revolution

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the economic landscape of world changed. The railroads grew from their first tentative lines in the 1820s to ubiquity by 1850. Rail traffic replaced most canal traffic and road traffic with faster transportation at a much lower cost. This rail traffic unlocked the capabilities of the interior of countries to produce goods for use far from the production areas. In the United States, this opened the entire mid-west of the country, where most food was grown, to export the food to the East Coast, where they could concentrate on industrial manufacturing.

Britain, Germany, and the United States lead the world in goods designed for export. As competition for growth grew, the British government began to pull away from free trade with the world, to the tentative use of tariffs which other countries were using.

Great Britain’s Dominance

Britain was the world's economic powerhouse in the 50 years running up to World War I. In some ways, even though economic growth was rising, it did not rise as fast as some other nations. Australia and the United States economically grew quicker than Britain but from a much smaller base. Their presence in international trade was much smaller. The British pound was backed by gold and was the world's common currency.

British investors backed much of the capital and corporate ownership of the United States and British colonies. With ownership and trade, Britain benefitted from their development.

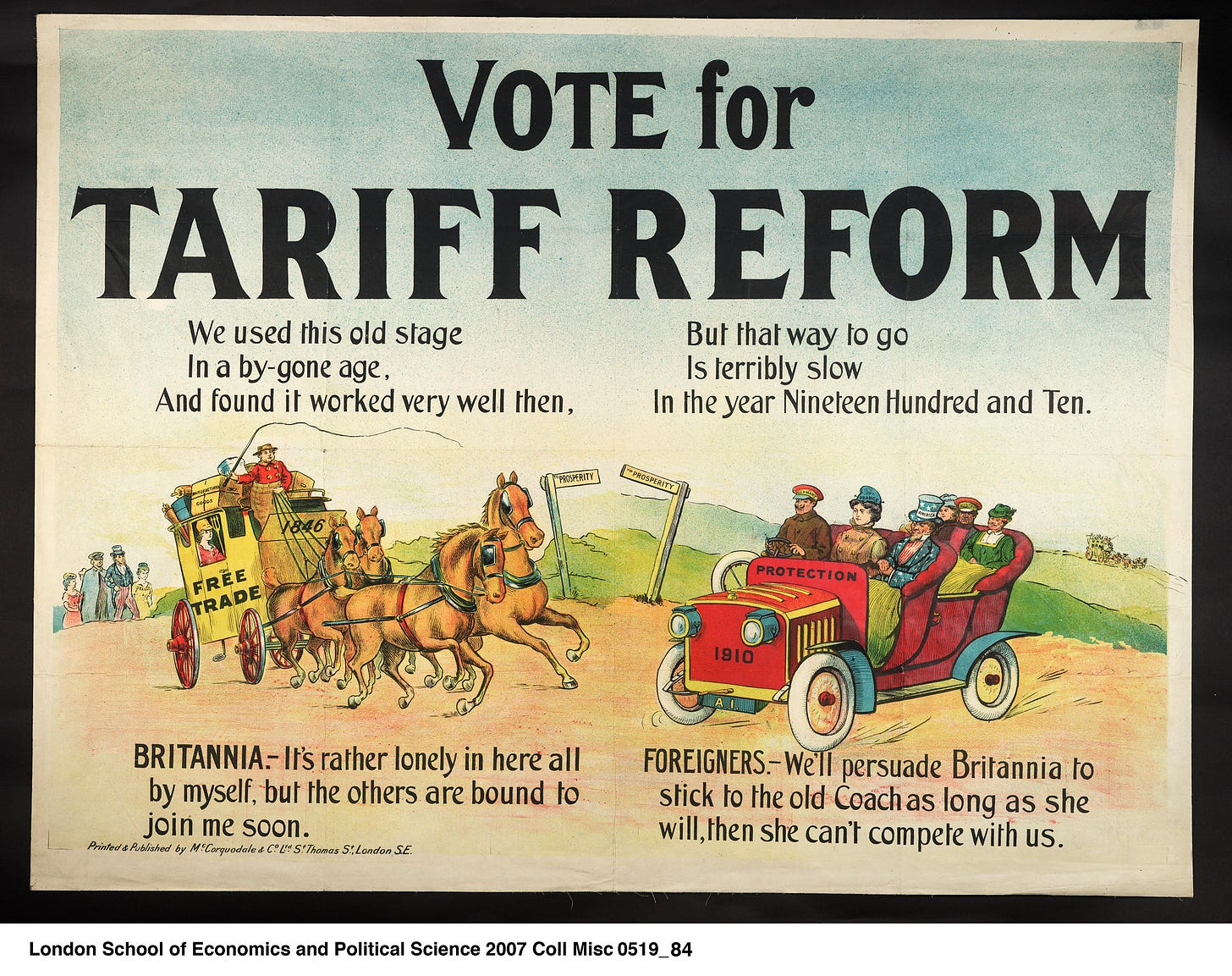

In the years before the war, British industries felt that free trade was no longer beneficial. Competitor nations were implementing tariffs and trade barriers that put British producers at a disadvantage.

Lobbying efforts by manufacturers of goods, coal, and farmers forced Britain away from its long-held free trade philosophy. Tariffs on British goods led to tariffs on imported goods, which led to conflicts with other nations like Germany and France.

France

France felt threatened by Germany’s rise. France lost the Franco–Prussian War in 1870-1871, which led directly to the creation of Germany. The head of the Prussian state spearheaded German unification. The war's outcome created a large, powerful nation that competed with France for influence in Europe.

France’s economic and industrial development lagged behind the Germans and British.

After the 1871 war, France enhanced its military system. However, as France fell economically further behind a united Germany, the French struggled with what to do. They entered into two alliances to contain Germany. First, they allied with Russia partly to contain Germany’s growth on the continent. France allied itself with Great Britain, which controlled the oceans to forestall issues with their colonial system.

At the onset of the war, France lost territory quickly to the German forces before digging trenches and holding positions. German militaries were better educated and armed. Using their expanded rail system, troops could be moved to the front much more rapidly than the French. The French were shown that they could be beaten by an opponent with a more advanced military and the greater economic strength to deal with the new way of war.

Germany’s Growth

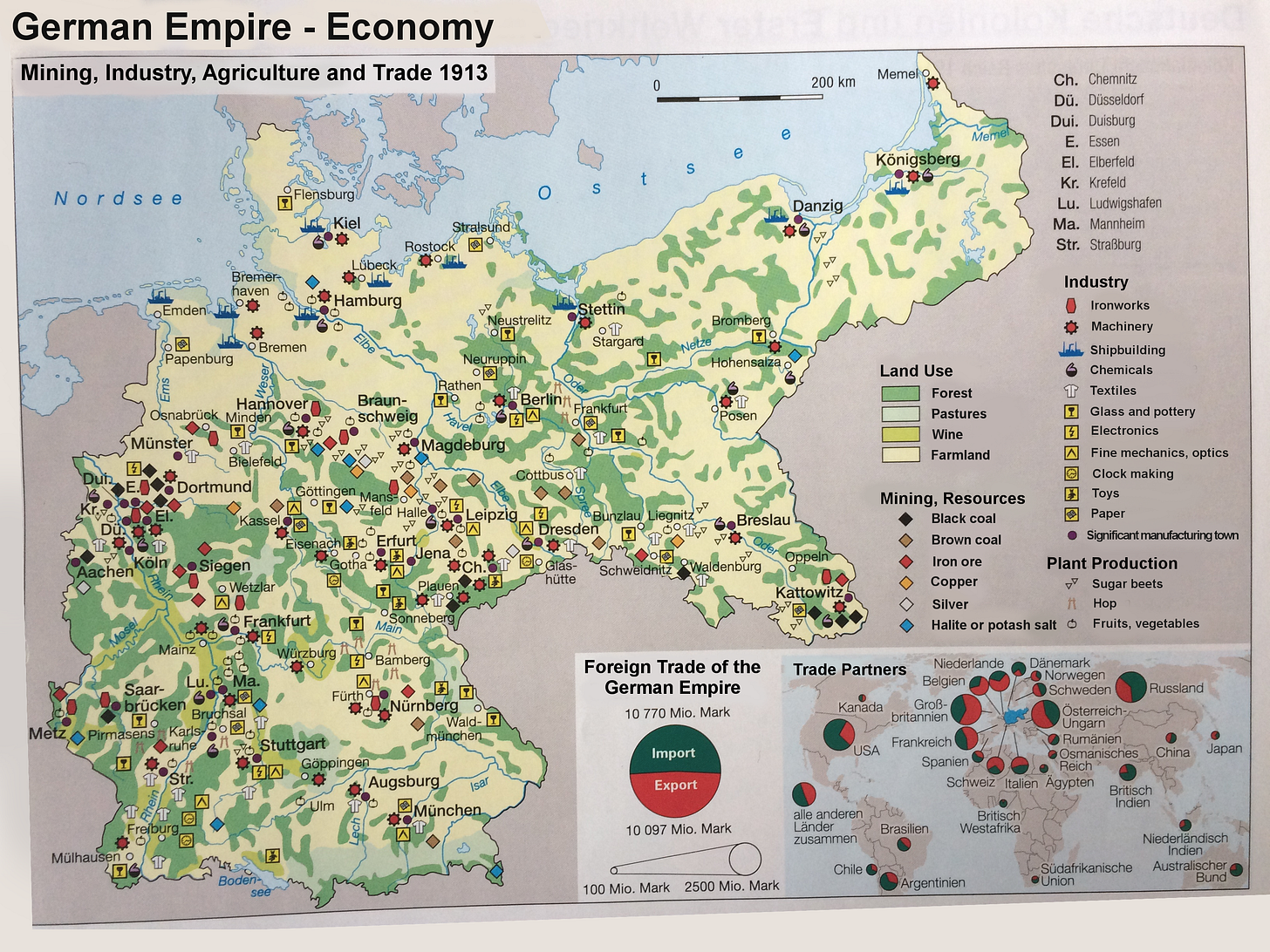

Germany had only consolidated into a single nation in 1871 when the northern German states combined to become a single empire.[1] Emperor Wilhelm and Chancellor Otto Von Bismarck led the Empire. The directed economy quickly grew into an industrial powerhouse. The new nation excelled in coal, iron, steel, and chemical production. By virtue of being built later than those in France and Britain, the newer factories of Germany were larger and more productive. The German Empire used some of this wealth to pioneer social programs like old-age pensions, medical care, and unemployment insurance.

Germany excelled in natural sciences like physics and chemistry. It also undertook industrialization more quickly than other powers. From unification through 1913, it built the largest rail network in Europe, had the largest economy on the continent, and challenged Great Britain by building the second-largest fleet in the world.

Germany’s rapid industrialization and economic growth threatened Britain’s economic dominance over the world as the two nations began to compete for markets and resources. Germany's tariffs and industrial policy challenged Britain’s extended use of free markets, leading to debate in England about the “German Problem.”

Germany felt hemmed in by both France and Russia.

Austria-Hungary and Russia

Both the Austrian and Russian Empires found themselves falling economically behind their rivals. They both tried to influence the new Balkan States to add their markets and resources to their economies. In the Balkans, they competed for influence, primarily through political means, not force.

Effect of Economics on Production

World War I was the first industrialized war. The nations involved had to produce a lot of machinery to prepare for and sustain the war effort.

The rivalry between the British and German Navy before the war showed the impact of an industrial economy. In 1871, when Germany was unified, it effectively had no navy. But by 1890, it had built the second-largest navy in the world, threatening British dominance.

Germany's wealth and technical prowess led its leaders to believe a short and decisive war would be easy to win. Germany had a significant and effective army equipped with the latest military arms and hardware.

Germany could outproduce either France or Britain alone. However, the French and British ultimately overwhelmed German production together.

Germany’s allies, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, did not have the benefit of new equipment and a large industrial base. The long-standing rivalry between Austria-Hungary and Russia depended on using proxies in many of its war aims. Bringing their large but less traditional forces against more modern armies of Western European powers led to an imbalance of power that the leaders did not fully comprehend. The relatively recent Napoleonic Wars were won by the forces of their and other allied armies. They failed to understand how quickly newer equipment would overpower them.

Many countries relied on cavalry at the start of the war. But new weapons, like guns and cannons, proved more successful despite the cavalry’s better mobility.

The lesson learned from WWI is that a strong and modern economy is one of the keys to winning a war and winning it quickly.

Russia

The production requirements strained the economies of all of the belligerents. For Russa, the strain of production and soldiers led to the overthrow of the Tzar and set the stage for the communist government.

Economic Aftermath of World War I

The allies of World War I learned how vital a strong economy was to the new type of war. This lesson dictated how peace would be imposed.

France and Great Britain wanted to stunt or delay Germany's reindustrialization. France pushed for punishing monetary reparations, geographic expansion, and the taking of many of Germany’s factories. Great Britain pushed for permanent naval domination by limiting Germany’s navy. Despite misgivings, the peace treaty was implemented this way, causing the economic crash in the new German Republic. The German people blamed the peace treaty terms for the financial disaster, and it brought on a new commitment for economic power and the ability to produce goods.

It is important to note that, up until World War I, most continental wars ended without these types of economic burdens on the losing power.

[1] The two southern Germanic states, Austria and Liechtenstein, did not consolidate with them.