There is a lot of discussion about climate change and its effect on animals adapting or dying out. It is not just a matter of migrating to a new region if the plants they depend on die out or can’t “move” as quickly. And we in the first world often wonder how to fix this.

This essay isn’t about that. But I think we can learn a lesson from the voluntary extinctions that man has caused to animals due to carelessness, greed, annoyance, or learned ignorance. Here I will look at the economic conditions that caused these extinctions and the geographic complications that enabled it.

At the highest level, there are only a few reasons that man purposely drives a species into extinction. They are exploited for food and cannot recover, killed as a predator that threatens us or our livestock, used as clothing or accidentally without knowing what we are doing, and by the introduction of predators.

Here are some of the significant species we have wiped out.

Dodo

The dodo was a large, flightless bird found only in Mauritius. It was discovered around 1600 and was wiped out by 1680. The Dutch, and later other traders, used Mauritius as a restocking stop on the routes to the Dutch East Indies. The dodo had evolved with no predators of the adult birds, and so they were unafraid of people. Unfortunately for them, the dodo was quickly caught and tasted good. Early theories were that man killed all the dodos for food, but science now believes dodos also suffered from the settlers’ introduction of pigs, dogs, and cats. The bird’s behavior also worked against them. When a Dodo was in trouble, for example, caught by a person, it would shriek. This sound brought other Dodos to the area to help the first, and they were subsequently killed. The widespread killing of the dodo so quickly meant it had no real time to adapt to the settlers.

Many people thought the dodo was also on other islands in the area and so locals could hunt them easily in Mauritius without fear of wiping them out. That was not the case. The last Dodo was spotted in 1680, but some probably remained in the wild for a few years later.

British Beavers (16th Century)

The British beaver population was wiped out in the 16th century. Beavers had been widely spread over England and Scotland. In fact, Eurasian beavers have been reintroduced in Scotland and England to improve local ecosystems.

The beaver in England was hunted for many reasons, and they combined to make beavers highly valuable. Their pelt is thick and excellent for outdoor clothing. Their meat was considered delicious and wildly sought after. Many landowners thought of them as vermin. Finally, and news to me, they produce a scent for marking territory from a unique anal gland. This creates a product called Castoreum.

Castoreum was used in flavoring, perfume, and “natural” raspberry flavoring. It was highly desired by a range of producers.

They were hunted to extinction for these traits. After they had been wiped out in England, trappers went to the United States, where the American Beaver was almost wiped out but saved by a change in clothing tastes in Asia, as fur from other animals moved into vogue.

Warrah / Falkland Islands Wolf

The Warrah was discovered on the Falkland Islands in 1690. Settlements and sheep farms were established in the Falklands, and by 1833, they were increasingly rare. The warrah was hunted primarily for its fur. Without natural predators, it was unafraid of people as predators. It was said a person could kill a warrah by holding meat out in one hand and a knife in the other.

The warrah was also poisoned in great numbers by sheep farmers who believed it preyed on sheep. Later investigations found sheep were not in the warrah’s diet at all. Farmers believed this tale because settlers could see them frighten the sheep. It is now thought the sheep saw warrahs as dogs and would run from them. These sheep then got stuck in bogs or swamps and died.

Since the warrahs were not afraid of people, and the Falklands had no forests for them to hide in, they were easy to kill. So easy in fact, the settlers killed them all.

Passenger Pigeon

The extinction of the Passenger Pigeon is a story that seems almost impossible. In the 1800s, the species' population was over a billion birds. But by the end of the century, there were nearly zero left. The last two known examples actually did in a zoo in 1914.

Passenger pigeons were subject to two different problems. First, they were hunted commercially for food. Their mass population and tendency to belong to huge flocks made killing them relatively easy. The demand for protein for a quickly growing nation increased the pressure on them.

The other reason could not have been easily understood by the 1800s hunter. We only recently discovered other reasons and theories. Passenger pigeons lived in huge flocks and adapted to communal living. The entire flock helped raise chicks and worked in concert to hunt food. Without large populations in a single flock, the population naturally shrunk when great numbers were hunted. This situation made the species very slow to recover, and isolated remnant populations died out.

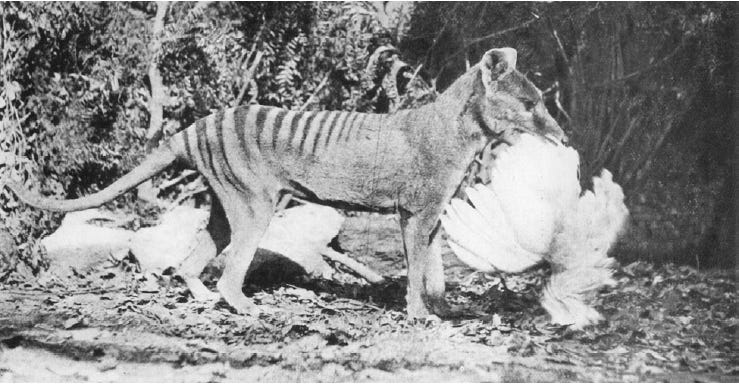

Tasmanian Tiger

The last known Tasmanian Tiger (Thylacine) died in a zoo in the 1930s. Despite its name, the “tiger” was an omnivorous marsupial who had evolved with slow-moving marsupials on the Australian continent.

The Tasmanian tiger lived on the mainland of Australia for thousands of years, and it probably killed out with the introduction of the dingo. The dingo was a better hunter and was a pack animal rather than the more solitary Tasmanian tiger. It is a better hunter and fighter and adapted quickly to Australia.

Even though the population was killed on the mainland, the species lived on in the Australian island of Tasmania through the 1930s. They were rarely seen but were blamed for the killing of sheep and chickens. The government, made up of local farmers and settlers, decided to cull the Tasmanian tiger by offering a bounty for those that brought in dead adults and a lesser bounty for pups. Thousands of bounties were claimed, and decimated the population of tiger was. The tiger also suffered from habitat loss, loss of prey, and the introduction of dogs by the settlers. Recent investigations show that human disease probably contributed to their demise, as it does with other Tasmanian animals. Today, authorities are working to save other marsupials that are subject to the same disease (chlamydia).

Some believe that a remnant population might still be found on the island, but no actual proof exists of this. At least not yet.

Great Auk

The saddest of these stories concerns the Great Auk. This large flightless bird grew up to 2 ½ feet tall. It lived in the northern Atlantic Ocean and bred on deserted rocky islands close to fishing grounds. The auk was not related to penguins in the South Atlantic. However, it did share some similarities. Auks mated for life, bred in dense colonies, and laid a single egg.

Unfortunately for them, the auk’s down was valuable, and its meat was editable. On land, they were clumsy and easy to kill. They were wiped out in Europe by the mid-1600s.

But the Great Auk lived on in the waters of North America and Iceland. The auks were revered and critical to many Native American populations. The European trappers who went to America for beaver and other animals used the docile auks as a convenient food source or even as bait when fishing.

The auks began to die off due to hunting and expanding Europeans in the Americas. By the early 1800s, it was clear that the auks were rare and dying out, which created a demand for the birds for zoos, from collectors of skins and eggs and trackers who could turn the now rare bird into cash from collectors. The demand wiped out the auks quickly. The last breeding pair was killed off Iceland in 1844. Sightings continued for a decade as the few left died out.

These are only some of the most famous extinctions. Scores more have occurred in the last 500 years.

What did this teach us?

Despite their sad outcomes, these species greatly influenced how mankind looks at some species. To save species, we now consider the number of individuals in a species, what habits it requires, and what we can produce to offset the needs of individuals and groups that depend on and/or profit from hunting them.

Are any species still in danger from mankind?

Many species are still very much in demand and threatened by human-caused extinction. Here are some:

The Greater Prairie-Chicken

The numbers declined to “near extinction” levels because they breed and live in the wild prairies. Their extinction nearly occurred not due to any desire for the bird itself, but for its habitat. Greed.

Rhinoceros

Rhinos are endangered and some entire species have disappeared because they were hunted for medicine. Rhino horn was believed to cure a number of disease and it still sought after for its purported ability to create stronger erections and greater virility.

The northern white rhino and the western black rhino are completely extinct. The Javan rhino has a very small population, all live in a single protected area. Sumatran rhinos only have about 30 individuals left, spread over two islands, Sumatra and Borneo. Folk medicine.

The American Bison (Buffalo)

Although there is now a large and stable bison population, most are descended from just a few herds in Canada. The reason for killing bison is pathetic. The American government killed as many buffalo as possible to deprive Native Americans of one of their chief resources. It nearly worked in North America and may have actually worked in the United States territory. When the Native Americans in the United States were essentially defeated, and they were herded onto reservations, nearly the entire country was bison-free. Combat.

The Elephant

Elephants have made a remarkable comeback. Hundreds of thousands of elephants in Africa were killed for their tusks. Their tusks are where ivory comes from. Ivory was used in art, piano keys, buttons, false teeth, fans and dominos.

In the case of East Asia Elephants, there was less pressure from man for two reasons. First, some Asian cultures have used Elephants for labor and transport for thousands of years. There, the elephant was seen as more than a provider of ivory. Secondarily, female elephants in Asia do not have tusks, so there was no profit in killing them. Greed.

There are still species threatened by man for food or money in areas with problems of hunger or poverty. Western attempts to save these with bribes or force conservation are challenging. The wholesale destruction of tropical rainforests is the process of wiping out species we don’t even know yet, but it provides funds for governments when the land is used for something else.

As a group, man is much better at saving animals today. However, our efforts usually involve large and photogenic animal protection like Condors, Golden Lion Tamarins, majestic Great White Egrets, Indian Lions, etc. These efforts are reasonably successful, but entire groups of less flashy animals are still lost all the time, now mainly due to habitat loss.

Mankind gains a conscious when saving animals now that were threatened by man in the past. But we still ignore the threat of extinction when it is not convenient for people or corporations, as with the Greater Prairie Chicken or the Pangolin.

I think as we move towards addressing our own needs regarding climate change, our focus on threatened animals will diminish. At least our willingness to spend resources that we might need to address our own survival will be severely tested.

The effect on the conservation of other species will not be of prime consideration.