Air Travel Before 1978

Domestic Untied States Regulation

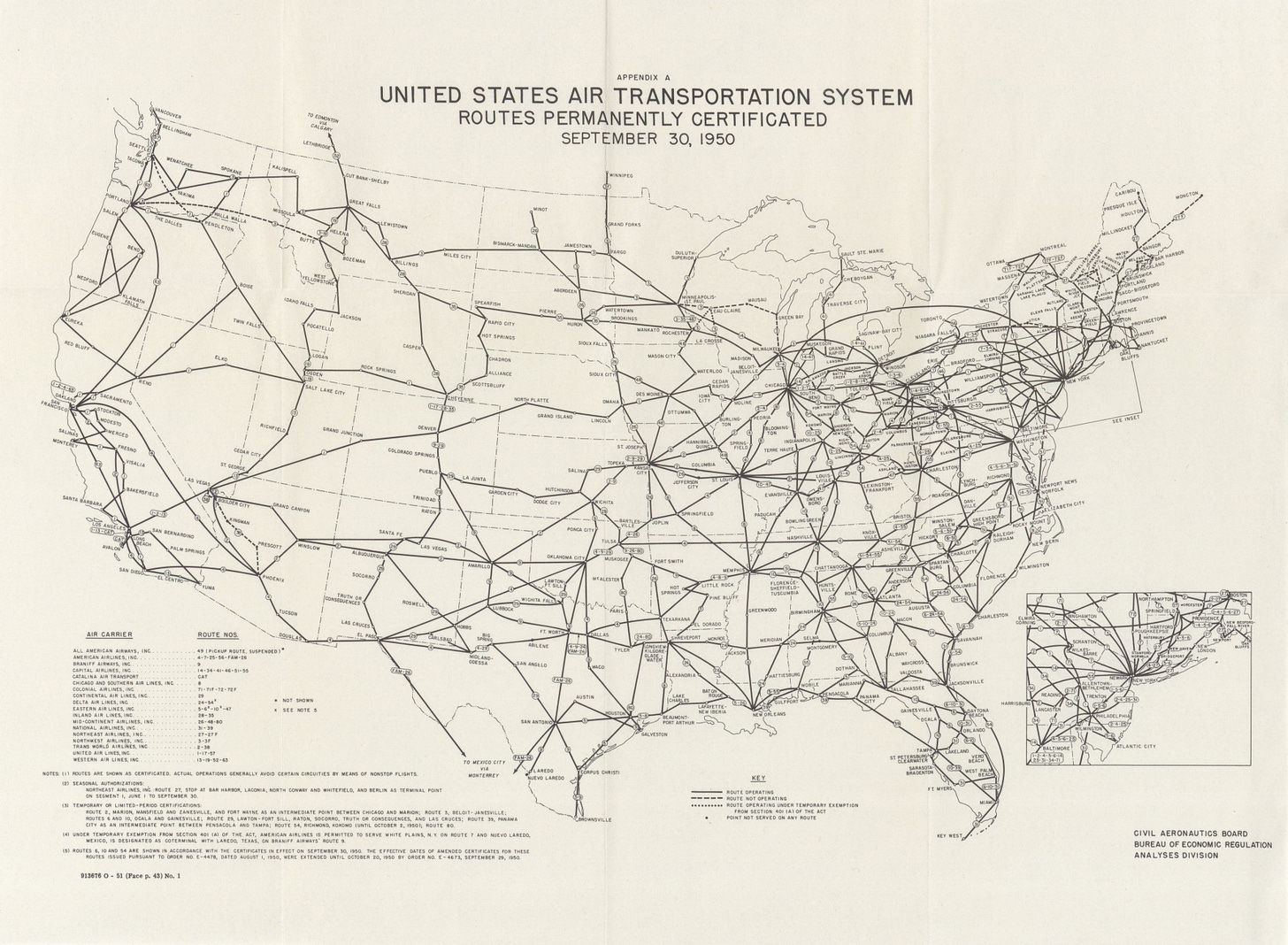

Starting in the 1930s, the United States worked to support and protect the new industry, flight. Originally this was done via governmental support for “air mail” to support the 4 mail airlines at the time: United, American, TWA, and Eastern. The Civil Aeronautics Board (“CAB” - forerunner to the FAA) was created in 1938 to take this regulation and extended them into the passenger space. The CAB regulated prices, regulated which airlines were awarded air routes, and worked to actively prevent new airlines from entering the competition. The idea here was to use government programs that protected this key industry for the nation. The government is currently using a very similar system of regulation to support energy creation via Wind and Solar industries. The airline regulation system was in place from 1938 until 1978. There were exceptions to this system that proved it was possible for the industry to operate more efficiently.

Exception: Interstate Flights

There was one major exception to the CAB rules, airline routes within a single state were unregulated (except for safety). This led to a few strong regional airlines in California, Texas, and Alaska.

The success and efficiency of these airlines were seen as “proof” that deregulation could be successful. These airlines built out profitable routes to Mexico, showing that expansion could happen internationally.

International Flight Regulation

International Flights were under the control of individual countries. In Europe, most countries had a national champion airline, like Air France or Alitalia, and they allowed one or two US airlines to fly into one or more destinations in that country, for equal access to cities in the United States. Nearly all these agreements were bilateral, between only the United States and one other nation.

Pan Am (Pan American Airways) was the regulation era preferred international flag carrier for the United States. This was the primary way Americans flew intercontinentally to Europe and Asia. Both carriers, the US and foreign flag carriers, were not allowed to continue the flights on to another domestic city. For example, if you flew Pan Am to Rome, you could not then proceed to Venice on Pan Am, you had to change to the national carrier. The price on the trip would be set by the two nations, and neither could change it to undercut the other.

Side Note

In the 1960s and 1970s you could get low costs flights from the United States to Europe through Icelandic Airlines (né Loftlelõir). The airline did not join the “International Air Transport Association”, so it did not have to use any set pricing. Because flights could only be carried out between two countries, this airline used to book one ticket from the United States to Iceland and a second ticket from Iceland to Europe. The fares through Iceland were significantly cheaper that direct flights because of their pricing system. The layover in Iceland could be as short as an hour, and people did not have to get off the plane. In this way it was one of the pioneers of low-cost flying.

After Deregulation

In the United States

The number and routes of US airlines after deregulation in 1978 grew quickly. Many old established airlines grew and flew new routes completing on price and times. Airlines like Piedmont, Air Florida, Braniff and Hughes Air West, expanded with varying degrees of success. New airlines also tried to establish themselves. Examples of now defunct airlines are: People Express, Trump Air, Presidential Airlines, and Royal West Airlines (later “The great American Smoker’s Club”).

But expansion and growth were severely curtailed in the early 1980s. First by a recession in 1980 which reduced the public’s ability to fly, and then by the firing of Air Traffic Controllers in 1981 by the Reagan Administration. Left with fewer available slots, many industry startups went bankrupt or had to merge with established airlines. Major airline mergers started in the late 1990s and continue today. The resulting major airlines still dominate in the United States because of the high entry costs.

New airlines now are focused on ignored routes and secondary markets. The route map of Avelo Airlines – first new airline in 15 years – shows the secondary markets or airports that are the focus of their investments.

One lasting result of deregulation is the explosion in air travel, and the low cost. In inflation adjusted numbers, almost all flights now cost much less than they did before regulation. The “average” price of a ticket has dropped 35% since the end of price controls.

In Europe

Internationally “Open Sky” treaties were signed deregulating air travel between the United States and many other countries. These treaties deregulated the “floor price” airfares between the two countries and allowed carriers to fly landing point onward from the arrival country to another stop. For example, now United Airlines can fly to Rome and then onward to Venice. British Airlines had a route that flew from London to LAX and then on to San Diego. Both routes were not possible until the Open Sky agreements.

The Open Sky agreements enabled prices to drop dramatically between the United States and Europe. It also changed the economics of airlines. National flag carriers had been protected in their home markets before Open Sky treaties. Given cost models set by the country, many of these airlines were not able to compete with new airlines with lower per seat and per mile costs. National Flag carriers that previously had national monopolies were forced to merge or restructure. Defunct national airlines include: Alitalia (twice), Sabena (Belgium), Austrian Airlines and Swissair. Pan Am also failed, one of their big problems was they had thrived under regulation but had no internal US feeder system to get to their hubs. By the time the airline was resolved this with domestic feeders, it was too late to save the carrier.

Offsetting the loss of national carriers, many lower cost airlines have risen (and some closed) in Europe. For example: Ryan Air, Easy Jet, Norwegian, Norse, Laker Airways, and Wizz Air.

Economic and Social Impact of Airline Deregulation

Airline deregulation has had both expected and unexpected results. The good probably outweighs the bad, but it has effects far beyond what you expect.

Lower Costs: Positive

The justification of airline deregulation was to make flying easier and cheaper for people. It is now much cheaper to fly than it was during deregulation. In inflation adjusted terms, real prices in the United States have fallen 44%. Here deregulation was a great success.

More People Flying: Positive

It may not seem a positive that more people are flying when you are waiting in a TSA line or trying to check in, but the number of passengers being able to fly has grown amazingly. In 1977 (the year before deregulation) airlines carried 240 million people. In 2019 (the last year before Covid) US airlines carried 853 million people. That is a growth of 255% versus the US population growth of 49%. That means more people than ever are flying both for pleasure and for business.

More Choice in Prices: Mixed

Before deregulation, there was a set price for a flight for coach, business and first class. Now there are a variety of classes and prices. There is economy, basic economy, economy plus, premium economy, business / first class and more. It is confusing and annoying but these choices do a much better job of providing the flyer of allowing flyers themselves to tradeoff between cost and amount of service. That’s on the positive side. On the negative side, there is a lot of confusion and anger about hidden charges and things that used to be free that are free no longer.

Revenue for Airlines: Mixed

Airline deregulation changed the profit model for airlines. Before deregulation airlines competed on amenities and reputation to attract passengers. After deregulation the model changed. As actual consumer prices decreased, the airlines have adapted. One way of doing this was to cut costs. Airline personnel will tell you that wages have not kept up with inflation onboard or on the ground. Another way to make money was to fill planes. Before deregulation planes flew at about 50% of capacity. Now airlines regularly fly well over 75% full. And that understates the changes because airlines now fly much larger planes with many more seats.

Deregulation has also incentivized mergers and take overs in the sector. Before deregulation, many airlines split US market. Today, after years of consolidation, there are 4 major airlines that carry 80% of US customers.

Point to Point: Consumers | Negative

Before deregulation the FAA ensured that every reasonably sized city would have air service. After deregulation most major carriers moved to a “hub and spoke” system. This consolidated flights and passengers, and then allowed the carries to “right-size’ their airlines. For example, Delta customers will often fly to Atlanta in a larger plane, and then switch to smaller regional jets and turbo props for the last mile to the destination.

Point to Point – Smaller Cities | Negative

The hub and spoke system has been very disruptive for smaller cities. Many small cities, like Cheyenne – the Capital of Wyoming – are left with minimal service. In downturns, the smaller airports are often at threat of closure or severe service cutbacks.

Hub and Spoke – Larger Cities | Positive

The cities which have been designated hubs, like Atlanta, Dallas, and Chicago, can now make more money by auctioning off landing gates and times. This provides extra revenue to the city which is provided via higher ticket prices baked into fares. This revenue is often used to update and upgrade facilities. Cities also benefit when airlines pay for upgrades to airports, enhancing the value at little cost to them. Extremely popular destinations with limited space, like Haneda in Tokyo or Heathrow in London, can charge exorbitant landing fees.

Barriers to Entrance: Negative (but getting better)

As noted above, four US airlines control 80% of the market. New low-cost airlines often startup, then shut down quickly. Low-cost airlines that are popular in the United States often get purchased quickly. However, there are some new entrants that have found a different way to succeed. One way is to fly point to point between smaller cities, like Avelo Airlines. Many of these save money by relying on only 1 or 2 types of aircraft, and often travel between underserved cities. For example, Avelo Airlines flys to smaller airports and cities like Kalispell, Montana, Eureka, California, Melbourne and Fort Meyers Florida.

European low-cost airlines often fly out of airports close(ish) to main cities, but with much cheaper landing fees and more slots. In the United States examples of these include Hartford, Connecticut, Long Beach, California, and Stewart, New York. Internationally some secondary airports are old military landing fields far from the city served, like Trevisio for Venice and Hahn for Frankfurt.

Summary

Airline deregulation has been a net positive good. It allows more people to fly at a lower price, despite the reduction of the number of airlines. It also increases competition on most routes.

It has yielded a more complex system where a person must do more research, but the results are great for travelers.